|

Ummugulsum Oh my dear,

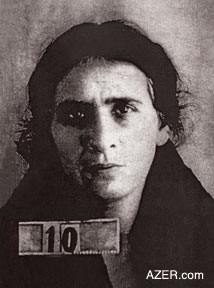

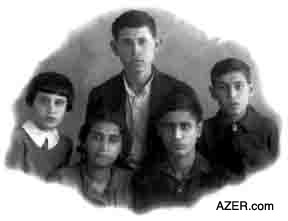

Above: Ummugulsum, as a young woman and later when she is in prison in her 30s. She has written the most compelling account of a mother's anguish for her children among all of the Azerbaijani writers who were repressed by Stalin. A big fight started. My ears pained me from the scandalous fight. This is what exhausts me most of all. It's not the first time. These fights. These arguments take place every morning and every night. Even though I try so hard to compromise and get on well with others, this filth affects me, too. Yesterday someone said to me: "You liar." This one word is such an insult to me. People call each other such foul names. It seems like the laws of nature have changed. The days are so long; 24 hours seems like it will never come to an end. After drinking tea, one of the women from another cell told us the bad news, which made all of us cry. She said that the NKVD [People's Committee for Internal Affairs and forerunner of KGB] was taking away the children from relatives of prisoners whose salary was less than 400 manats. This news struck me like a bolt of lightning just as it did the other women who had children. Now the children who have lost their parents will not even be able to see their aunts or uncles. They are going to take those children to a place where they won't know anyone, and where they will have to face so much trouble alone. They're going to a place where they won't be able to tell anyone of their grief or pain; where they'll have to live with grief swelling up inside their young innocent hearts and making them cry inside. We have no other alternative but to cry. It's good that these tears did not continue for too long. Another woman started talking. Her news was totally the opposite of the first woman's. She said that she had heard that all the women would be freed from prison and exiled with their children. This made us all start crying again, but these were tears of happiness. In my opinion, I suspect that neither of these stories is really true. February 4, 1938 I haven't been feeling very well lately. I'm in an advanced stage of anxiety. My heart is burning. I haven't received a single letter from my children for more than two months. I only get letters and parcels from Sayyara. How could it be that my children don't write me anything? I can't imagine this. They wouldn't intentionally let me worry like this unless something bad had happened to them. Even Sayyara does not mention the children in her letters. All she says is: "The children are OK, don't worry about us. We're doing fine." This might be a lie. I sense that Ogtay may have been arrested and my other children are not writing anything so that I won't know about it. Horrible things come to my mind. God, what a torment I'm in. I had told Gumush to sew a handkerchief by hand and send it to me. She told me she would. Why hasn't she done it yet? I beg for photos in every letter. God, what is happening?! My heart is exploding I really feel like my heart burst out of my chest. Ohh! I can't stand this anymore. Gumush's teary eyes, Toghrul's pale face are always in front of my eyes. Who can deal with so much grief? Five days ago I had a dream: a lot of women were lying near each other on the seashore. I was among them. Gumral was standing apart from them. She was wearing a dirty, torn undershirt, her face was tired; she was crying and wiping her face with her hands. I saw her and said: "May mother be sacrificed for you! Go wash your hands in the water and come." I said, "May I be your sacrifice. Let me take you in my arms." In my dream, I stood up. But at that moment I woke up. Since that day I've been so worried about Gumush. I don't know what to do. Once I dreamed of Toghrul. He was coming from somewhere. He had lost a lot of weight. He started to cry when he saw me. I was crying, too. We hugged each other. But that dream made me very sad. These scenes never leave my eyes. I dreamed of my mother and father last night. Every time I dream about them, something good happens. I wonder what will happen today.  Today is a very important day. I must write today. Early in the morning there was a loud noise coming from the cell opposite ours. We all got up and went to the door. What a painful scene. It seems that Dilbar, the wife of poet Mikayil Mushvig, is losing her mind. Left: The four children that Ummugulsum Sadigzade left behind when she was sent into exile to Kazakhstan for eight years. The children were left in the care of her 21-year old niece Sayyara Rezayeva (1916-2002) seated here in the photo. Clockwise from left: daughter Gumral (1929- ), son Ogtay (1921- ), Toghrul (1926-1995), and Jighatay (1923-1947). Later both Ogtay and Jighatay were sent to hard labor camps since their father had been accused of being an "Enemy of the People". Jighatay did not survive the camps and died at the age of 24. Their father Seyid Husein was executed in 1938, but they didn't learn of his death until 18 years later. We heard this news yesterday. But the significance of it wasn't very clear. We all thought that she was just upset about something. Yesterday, she didn't look like she was going mad. In fact, she was trying to console me. She was saying: "What can we do, we must be patient. We will have to deal with situations that we've never faced before" Yesterday she was feeling pretty good. But today the situation is totally different. Just like every night, Dilbar didn't get any sleep last night either. As well, she became very angry, insisting that everyone play and sing. Then she started talking to herself and whining. She wrote a letter of complaint and wanted to be released from prison. Finally, she grabbed a woman by the neck and tried to choke her. Now the women are gathering around the door of the cell and making a lot of noise to attract the guard's attention. The women want Dilbar to be taken away from there. Some supervisors, guards, and a doctor's assistant have come to their cell.

February 29, 1938 I didn't sleep last night. All of us woke up this morning in a bad mood. Dilbar has totally lost her mind. They took her upstairs to the prison hospital and put her in isolation right above our cell. Yesterday, they gave her an injection to calm her down. She slept until night. But then, she woke up and started again. The whole night until the morning she was running around nonstop, hitting her head against the walls, stomping her feet on the floor, and trying to say something. She was singing. She was complaining about something. It was not clear what she was saying, but you could understand some of her words. Dilbar was mourning and repeating over and over again in a sad rhythm: "Poor Dilbar orphan Dilbar lonely Dilbar" Then she started speaking in her normal voice: "Let my Mushvig come, let my father come Go knock on the door and tell my father to come and take me They say that I have lost my mind I must die for my lover Hey, invisible God! They say that You don't exist, please help me!" She was talking with Mushvig. She was looking at him and patting his face as if he were with her in the room. Then she threw herself down on the bed and screamed so loud. Then she got up again, and ran around. Dilbar's condition made us all so miserable. She was our dear poet Mushvig's lovely, beautiful Dilbar. Now she had gone crazy on that dark day. Everybody was talking about her. Rumor has it that they've tied her hands behind her. March 14, 1938 Today is parcel day again. I didn't sleep last night. Outside, a strong wind is blowing. The weather is very cold. You can hear the voices of women who are waiting in a line to offer parcels. They have been waiting in line since last night. Who are they? Tiny, innocent babies, old and tired mothers. Personally, I'm against mothers and children having to wait in line during this cold weather. The severe wind is enough to worry us all. Probably, my mother-in-law, Jighatay and Ogtay were also freezing in that cold until they turned blue. I wait impatiently for the morning to come. Only then will these miserable people waiting outside be able to escape from the freezing cold. Morning has come, now it's time to receive our parcels. We are waiting again for the list of names. But somehow there is no list. We asked the supervisor what happened. He said that there would not be any parcels today, because they sent eight special trains last night. This news struck us like lightening. What did it mean? What did transportation have to do with our parcels? It means that our mothers and sisters froze in that cold weather all night long waiting to turn in parcels for us and then they had to return home so distressed. These words made us so upset. Everybody in the cell started to cry. Who would take care of our children if they caught cold in that freezing weather last night? Who would call the doctor for them? Who would put a kerchief on their feverish forehead, who would make them change their sweaty clothes, who would offer them warm soup? Isn't it enough that as innocent women we have been rotting here for four months. And yet, they still torture our children and relatives, and torment us psychologically.  Although Bakhshaliyev came, he could not stop the noise. The anxiety continued. Bakhshaliyev said: "You will not get any parcels or letters because of your unruly behavior." We replied: "Don't you have any pity on our children and our old mothers? They froze in that cold weather last night and you sent them back home without being able to see us." He cursed us: "May your mothers and children go to hell." We decided to go on hunger strike and not eat anything. Then we would call the NKVD head prosecutor and demand to "be released, because we are guilty of nothing; we're innocent"; otherwise, we would continue our hunger strike. We all went on hungry today. In addition to our cell, the women in nine other cells went hungry as well. March 16, 1938 We are continuing our hunger strike. My knees are shaking when I stand up, and green and red flash before my eyes. It's night. No one listens to our complaints. No one cares about our grief. We decided to eat because, otherwise, we would lose the only thing we had - ourselves. April 17, 1938 They are impatiently waiting for the list. But the names of the people who are waiting for the list are not on the list. On the contrary, they are reading the last names of people. What is this? We don't know. We ask each other what is going on. We received an unusual answer. We found out that Azerbaijanis are known not by last names, but by their first names. Other nations go by their last name. For example, in our cell we had some Russian women whose last names were Azeri because they were married to Azeri men. They were called by their last names, not by first names. At first we couldn't believe this. Then we realized that it was true. April 18, 1938 Today, again there were people who had to wait but did not get to meet anyone. It's good that my first name and last name ["U" and "S"] will be called on the same day. I will be able to get a meeting on the 21st. That's just three days from now. It will be like a holiday for me. April 20, 1938 Today it's five months and ten days that I have been in this Bayil prison - 160 days! It's been that many nights that I have not seen my children. When I think of their faces, I feel like I see them in a mist - like behind a curtain. I'm starting to forget what their faces look like. But I remember Gumush's face. I remember her face the last time I saw her. I think that even if years pass, I will never forget the expression on her face the last time I saw her.  That night I woke her up from her sweet dream and I was crying while carrying her in my arms to the other room. Her unkempt hair was all over her face. Her cheeks were burning. She was crying. I was holding her in my arms, and her eyes were filled with tears, shining like big diamonds. When I put her on the bed to sleep, the diamond tears fell on her cheeks, leaving streaks on her cheeks. When I looked at her for the last time she was still lying on her back and crying, and looking at me with those big innocent eyes filled with tears. I will never forget that scene until the day that I die. And I remember very clearly her hair when I woke my baby up and took her to the other room, and my Toghrul's ashen face, and my Gumush's teary eyes. The meetings have started already. The meetings are separated in four groups according to last names. The women can meet with their families on the days when their last name group is assigned. On April 3rd, the supervisor came and gave a meeting schedule for each group. This news was like a holiday for us. Tears of happiness streamed down my cheeks. The first group's meeting was scheduled for the 14th. There were seven people in our cell that were assigned to that group. There was great joy and happiness in our cell. It reminded me of a bayati: The ashug will make a game The meeting day will be our

holiday, too! This will be the holiday for the elderly mothers

with white hair who are exhausted, longing for their daughters.

It will be a holiday as well as for young mothers who should

be living the best years of motherhood with their sweet and playful

children. The women who get to meet their loved ones tomorrow

could not sleep the whole night. Morning came. Everyone was waiting

for the list just as they do on parcel days. It was 12 o'clock,

but still no news.

The door opened. We left the cell. Along with women from the other cells, we waited at the door that opens to the outside. We waited, but they didn't let us out at once. This waiting exhausted all our patience. Finally, after a special inspection they let us out into the yard. I told myself that I would not cry, but I could not hold back the tears. We passed the first courtyard and arrived in the second one, which was where the meetings were to take place. There was a big door with wooden bottom and iron bars. You could see the heads of many people on the other side of those bars. My children were probably there, too. My heart and my eyes were doing their work. At first, everything seemed hazy, then I saw more clearly. I was so ready to see them not only with my eyes, but with my soul and my whole being. The big door, which separates us, opens. We thought that they were letting the people in. But these were just the prison workers who were coming through the door to go to work. Again, they made us wait. We waited there for nearly an hour. Suddenly one side of the door opened. People were hurrying to get inside. In this crowd everyone was looking for her or his loved one. In that crowd, I saw my Ogtay who was searching for me with his eyes. I couldn't believe my eyes, was I really seeing him? After hugging Ogtay, I greeted Birjabaji. Then I saw my little Gumush, standing in the corner. But she had changed beyond recognition. She had changed so much that I did not even recognize her. I would not have recognized without looking very attentively if she had not been standing next to Ogtay and wearing her coat and scarf. She was not the same Gumush as I had left behind back home. She had lost so much weight. Her cheeks were sunken. Her face, pale. And her eyes stared wide open. This child did not look anything like my lively, round- faced, playful, cheerful, chubby cheeked little Gumush. That means my absence had brought on this condition. How can my heart stand this scene, oh?! I want to shout with all my strength: "Why did my Gumush become like this?!" Toghrul had lost a lot of weight, too. But his condition was relatively better than my little girl's. He had become sad and silent like Gumral. I hugged my three children with all my being. They told me that Gumral became so skinny after she had the measles. I did not believe this. My child's appearance really disturbed me because I could not imagine such an illness. She had totally changed. In addition to losing weight, she had become taller, and her hair had grown longer and now was parted over her forehead. I looked at her face again, and I could see that she was beginning to resemble my husband Seyid Huseyn more and more. This girl that never looked like her father suddenly reminds me of a photo of her father when he was 20. All the important lines on his face are reflected on Gumral's face. I see Seyid Huseyn in this sad and innocent face. Birjabaji had become old. Ogtay seemed OK. He had grown into a young man. Jighatay standing behind those doors gives me another glance. The diary ends here. Ummugulsum's

Memoirs were abruptly cut here. No one knows the reason. Most

likely, she had no more paper to continue, or, perhaps, the pages

which followed were lost. Or perhaps, prison authorities forbade

it. No one will ever know. |