|

Winter 2005 (13.4)

Pages

58-63

Azer Alasgarov

Hardships Endured At Home:

When the Men Were Sent to Siberian Labor Camps

by

Fatma Alasgarova, wife

Fatma Alasgarova (1926- ) was the wife

of Azer Alasgarov (1926- 1995), a member of "Ildirim"

(Lightning), a student group that advocated the broader official

usage of their mother tongue - Azeri. This group sought to take

an active role in the development of Azerbaijan after World War

II, but actually they didn't manage to succeed because the government

was so repressive. Fatma Alasgarova (1926- ) was the wife

of Azer Alasgarov (1926- 1995), a member of "Ildirim"

(Lightning), a student group that advocated the broader official

usage of their mother tongue - Azeri. This group sought to take

an active role in the development of Azerbaijan after World War

II, but actually they didn't manage to succeed because the government

was so repressive.

Fatma was only 22 years old and had only been married four months

when her husband was arrested in 1948. She was totally oblivious

to the fact that he had been a member of any political group.

His arrest came as a total shock to her. He was sentenced to

10 years of hard labor in Siberia.

Fatma's story provides a perspective on the trauma that women

faced when their loved ones - husbands, fathers, and brothers

- were arrested. We often focus on the accused victim, forgetting

other family members whose lives were also turned upside down.

Women were often stripped of their economic source. Invariably,

they were encouraged by family members to seek divorce. In Fatma's

case, which was very typical, she was branded as a wife of an

"Enemy of the People" which prevented her from enrolling

in graduate studies and getting a job. Even when she divorced

her husband who was in exile, the stigma did not go away.

Fatma's husband was one of the lucky ones who survived the harsh

years of exile. He received a 10-year sentence in 1948. Azer

returned home in 1955 - seven years later. Stalin's death in

1953, led to his being released before finishing out his sentence.

The couple reconciled and married again. But those seven years

of separation were incredibly difficult. Here Fatma reflects

upon the incredible obstacles and uncertainties that they faced.

I had no idea that my husband

had been involved in any kind of political activities. Thus it

came as a total shock when NKVD agents knocked on the door in

the wee hours of the morning and took my husband away. [NKVD

in Russian means Narodniy Komitet Vnutrennix Del, which translates

as the People's Committee for Internal Affairs. This state mechanism

was the forerunner of the KGB]. We had only been married four

months.

I was born on April 27, 1926, in Shaki - a picturesque town located

in the foothills of the Caucasus in northwestern Azerbaijan.

My father worked for the government but had died at the age of

45 during the Azerbaijan Democratic Movement in Iran. Mir Jafar

Baghirov, First Secretary of the Communist Party in Azerbaijan

had sent him there. I was lucky that mother was alive.

After

graduating from high school in 1943, I was accepted at Baku State

University in the Philology Faculty where I enrolled in Oriental

Studies with a concentration in Persian language studies. After

graduating from high school in 1943, I was accepted at Baku State

University in the Philology Faculty where I enrolled in Oriental

Studies with a concentration in Persian language studies.

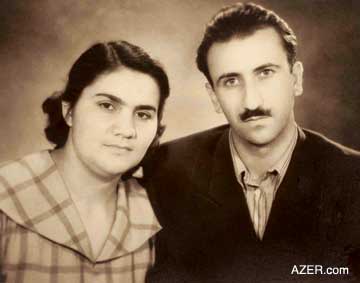

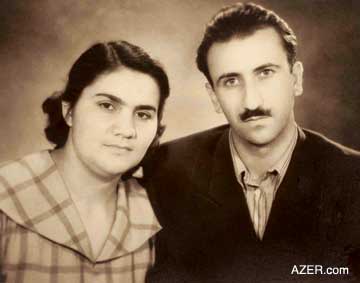

Left: Fatma with her husband Azer Alasgarov.

Photo: Family of Azer Alasgarov.

I graduated in 1948.

Actually, my husband Azer and I had studied together for five

years.

After graduating, we married a few weeks later on July 7th. But

in the early morning hours on November 6th, the NKVD was pounding

on the door. They had come to arrest Azer.

A few days earlier, Gulhusein Huseinoghlu [Abdullayev], who also

had studied with us, came over to the house on two occasions,

looking for Azer. I had no idea what they talked about, but when

Azer came back to the house, I noticed that he was looking miserable.

I asked him what had happened, but he wouldn't tell me. For days,

he wouldn't eat and he seemed so depressed.

A few days passed. Gulhusein, again, stopped by to see Azer.

Again, I had no clue what they talked about. Again he became

very pale and wouldn't eat anything. He started losing weight.

I didn't understand why he was so pre - occupied. He wouldn't

tell me. At that time we were living in the apartment of Azer's

grandfather. We were on the third floor; they occupied the second.

Azer's father had passed away when he was young. He had been

arrested and died in prison four years later. They were five

boys and two girls in his family. The sisters had married. Since

the older one had died, Azer's mother and grandmother were taking

care of her two children. Azer's mother also worked as a cook.

The uncles took care of them financially. With his mother working

all day long, there really was no one to raise the children.

None of Azer's brothers had gone on to get a higher education,

but Azer himself had always loved to study.

|

"I'm convinced

that we ourselves are to blame for much of this evil that befell

us. People betrayed one another. If someone didn't like you,

he would go and report you. The next day you could be arrested.

Betraying others is still part of our psychology today."

- -Fatma Alasgarova,

whose husband was arrested and spent seven years in prison camps.

|

The Raid

The guards were very punctual. They came directly to our apartment

at exactly 3 a.m. - October 23, 1948. Azer opened the door. They

showed him some paper, which I learned later, was the order for

his arrest. There were four of them. Two from the NKVD. The third

was our neighbor who served as a "witness"; the fourth

person was from the MIS [Apartment Operation Office which manages

the properties in any particular region].

Azer told me that they had come to take  him

and that I should get up and get dressed. I tried to slip out

of the room and run downstairs to tell Azer's brother that they

were taking Azer away, but one of the NKVD officers blocked the

doorway and wouldn't let me leave the room. him

and that I should get up and get dressed. I tried to slip out

of the room and run downstairs to tell Azer's brother that they

were taking Azer away, but one of the NKVD officers blocked the

doorway and wouldn't let me leave the room.

Then

they started searching the house. Since we had only recently

married, we didn't have much furniture. Then

they started searching the house. Since we had only recently

married, we didn't have much furniture.

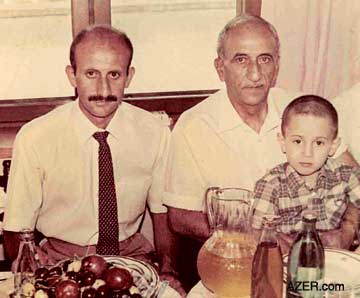

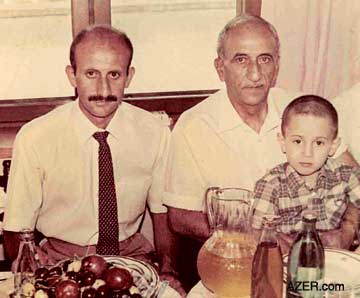

Left: Azer with his son and grandson (1980s).

Photo: Family of Azer Alasgarov.

Azer had told them that he didn't have anything. They searched

the whole house until six o'clock that morning. They couldn't

find anything except some notes that I had taken from my Persian

class.

Seems they thought Persian was really Arabic [of which they were

highly suspicious because the Koran is written in Arabic].

At the university we had had a teacher - Mubariz Alizade - who

lectured in Persian. His literature classes were so wonderful;

we never tired of them. Naturally, I took notes in Persian. The

NKVD found these notebooks and confiscated them. They also found

some of Azer's personal photos and took them, too. They wrote

down the basic items that we had in our apartment but, really,

they didn't take much else.

It seems that Azer used to organize meetings at his parents'

apartment especially when they weren't at home. I later learned

that sometimes even when his mom was there, he and his friends

would gather, but she didn't have a clue as to what was going

on.

All this had taken place before we were married. A small group

of guys had formed a group they called "Ildirim" (Lightning),

but they had not continued their activities after we got married.

In 1944, they had sent a letter to the well - known poet Samad

Vurghun, asking for his support. But when they didn't hear anything

from him, they suspended their activities. That was four years

earlier. That explains why I didn't know anything about this

group.

Actually, it wasn't until half a century later - that I found

out much about this group called Ildirim. Academician Ziya Bunyadov

gained access to the KGB archives after Azerbaijan became independent

and wrote the book "Red Terror" [1993] which included

the text of the trial of the members of this group. Ildirim was

a group of guys advocating the wider official usage of the Azeri

language as opposed to Russian. That's all. The group had never

really succeeded in its goals. Just talk.

During the trial, the judges exaggerated everything and brought

serious charges against the members of Ildirim, alleging that

they were trying to separate Azerbaijan from the Soviet Union.

There were so many lies: they accused the Ildirim members of

having organized underground tunnels and of close ties to Turkey.

But these things weren't true.

These young guys were simply hoping for some leadership from

Samad Vurghun. They wanted him to head their organization. The

letter they had written him dated May 11, 1944, somehow ended

up with the NKVD four years later exposing the group. All seven

guys were arrested.

After the NKVD left with Azer, I ran downstairs and told his

family what had happened. They thought that some mistake had

been made. "Azer would never have done anything to get arrested,"

they insisted. "He was educated and smart. He wasn't a criminal.

There has to be some kind of mistake." I later learned that

even Azer's family didn't know anything about Ildirim and that

Gulhusein, too, had been arrested that same day.

Then I went to my aunt's place. My father had a friend - Colonel

Padarov, who  worked

as the head of the Political Issues Investigation Department

at the Committee for Government Security (KGB). Since my father

himself also had worked for the government, we had often visited

this official because they were family friends. So my aunt, her

husband, and I went to see them. We told Padarov about Azer.

He started to cry. Then he kissed my forehead but he didn't say

anything. worked

as the head of the Political Issues Investigation Department

at the Committee for Government Security (KGB). Since my father

himself also had worked for the government, we had often visited

this official because they were family friends. So my aunt, her

husband, and I went to see them. We told Padarov about Azer.

He started to cry. Then he kissed my forehead but he didn't say

anything.

Padarov

and my aunt's husband stepped into another room and started talking.

When we left, Padarov hugged me and told me not to worry. On

the way home, my aunt's husband told me that since Azer's arrest

was a political case and related to political activities, Padarov

would not be able to help. Such cases were outside his jurisdiction.

Besides, those who assisted political prisoners could run into

trouble themselves. Padarov

and my aunt's husband stepped into another room and started talking.

When we left, Padarov hugged me and told me not to worry. On

the way home, my aunt's husband told me that since Azer's arrest

was a political case and related to political activities, Padarov

would not be able to help. Such cases were outside his jurisdiction.

Besides, those who assisted political prisoners could run into

trouble themselves.

The only thing that Padarov could do was to prevent the NKVD

from interrogating me as well. Actually, that was very important

because many wives of political prisoners were also later arrested

and sent into exile. It didn't matter that they had committed

no crime. So many women had to cope with such tragic situations.

Then we broke the news to my mom in Shaki. She came and took

me back home with her. That was November. I got a job there,

working as a teacher of Azerbaijani language and literature.

The Gulag

See ELENAFILATOVA.com - Excursion to Gulag

Photos below show part of

the Gulag system, a vast network of thousands of camps that extended

across the entire Soviet Union and which flourished under Stalin's

regime.

Many camps were located in Central Asia and Siberia and provided

free labor to develop wilderness areas, especially the natural

resources such as timber and gold. Now these camps are abandoned,

overgrown and accessible only by helicopter.

Photos

1. Poster says: "I fulfilled my quota, did you?" Meeting

the daily quota was rewarded with an extra ladle of broth.

2-4. One of the camps in the vast forests (taiga) of Eastern

Siberia.

5. One of the bridges built with prison labor which was never

used as Stalin died before its completion (1953).

6. Abandoned and rusted out steam locomotive.

7. To connect the two towns of Igarka and Salechard required

1,263 kms of tracks. Only 900 kms were completed. An estimated

300,000 convicts died while building these tracks between the

years 1949 - 1953. Now these tracks lead to nowhere.

8. Barbed wire. It was nearly impossible to escape the camps

because they were surrounded by barbed wire, watched by guard

dogs and located so far from any other settlements.

9. Bottle of vodka. Guards often sold vodka illegally to prisoners.

10. Typical pan that prisoners used to receive their food. The

prisoners kept these pans with them.

11. Spy hole so the guards could always look in on the prisoners.

12. The barracks held two layers of plank beds which could accommodate

120 prisoners.

13. Steps leading to one of the prison barracks.

The Trial

After a while, we learned that Azer and other members of the

Ildirim group would be put on trial in March the following year

- 1949. But they didn't tell us the exact date. It turned out

that Azer and his friends were trialed on March 21-22 (Novruz,

First Day of Spring), but we missed it all. We arrived in Baku

a day or two later because we didn't know. The trial had already

ended. Azer was sentenced to 10 years in exile. Actually, even

if we had been there, we would not have been allowed to be with

him during the trial. No one was allowed in. No one witnessed

the proceedings.

We didn't even know where Azer and his friends were being kept

all those months. Perhaps, it was the KGB prison in central Baku,

but we didn't know for sure.

People told us that after the trial, Azer and the other members

of Ildirim were hauled away in an open truck. A large crowd had

gathered. There were many young people and students. Since it

was Novruz holiday, people were trying to pass them baked pastries

like pakhlavas (baklava) and shakarburas by tossing them into

the truck. The Ildirim members were handcuffed to each other.

They said that Ismikhan Rahimov had stood up and with a raised

fist, shouted to the crowd, "Long Live Azerbaijan".

And then the truck had disappeared out of sight.

Occasional Letters

After Azer left for exile, I didn't hear from him for a while.

They were allowed to write letters to their families only twice

a year. We loved each other so much. We had been so close but

he never addressed any of his letters to me, except once. Perhaps

he was afraid that his letters would get me into trouble. He

used to write to his mother and so I read those letters. Frankly

speaking, he didn't say anything of importance in his letters.

What could he say? He used to write: "I'm here. I'm working."

Things like that. Once he wrote a joke, intended for me: "There

are no 'marfushas' here" (meaning no Russian women). I'm

sure he didn't want me to be worried or get jealous. It was a

joke. I knew what labor camps were like.

During those seven years of his exile, I only received one letter

from Azer. Unfortunately, it got lost while we were moving from

one house to another. He wrote that he was sorry that he had

made me so unhappy, and he apologized to my mother for what had

happened.

Difficult Separation

Those days when Azer was in exile were so difficult for me, too.

Keep in mind that I was only 22 years old. It was so hard to

bear Azer's absence from my life. In addition to all the unknowns

about his whereabouts and his situation, I also felt that I was

being followed - that someone was constantly watching me. And

people shunned me so much. That was the hardest part.

Once, I remember having to take a philosophy exam. Many students

were waiting in line. Finally, my turn came. I stepped inside

the classroom only to hear the assistant announce: "Professor,

do you know who this is? She's the wife of an 'Enemy of the People'

- just to let you know." I ran out of the room and burst

into tears. I couldn't stop crying. I wasn't allowed to take

the exam. Those days were so stressful. I couldn't sleep at night.

The next day I went to the Scientific Research and Pedagogy Institute

and spoke to the director about the situation. Finally, I was

allowed to take my exam.

Then my family put pressure on me to divorce Azer. Everywhere

I went I was known as the wife of an "Enemy of the People".

I couldn't advance in my work. I couldn't get accepted in graduate

studies. Always the doors were slammed in my face just because

of my association with Azer.

I didn't want to get a divorce. I was so crushed and depressed.

But, what to do? Azer's sentence was for 10 years and who knew

what would happen. So many people never returned from those camps.

Finally, I yielded to my family's wishes. I didn't know what

else to do. And so, I officially divorced him just to be able

to continue my studies.

In those times whenever you got divorced, you had to give public

notice in the newspaper. I really didn't want to do this, so

I had our announcement published in one of the Armenian newspapers

so that none of our friends could read it. I didn't want people

to know about it. I was so deeply broken and confused about it.

Divorce seemed so wrong since we loved each other so much.

I still

had problems getting accepted into post-graduate studies even

the third year after the divorce had gone through. Finally, I

was able to continue my studies in 1952. I still

had problems getting accepted into post-graduate studies even

the third year after the divorce had gone through. Finally, I

was able to continue my studies in 1952.

Left:

Poet Bakhtiyar Vahabzade

pinning an honorary medal on Azer Alasgarov. Azer received two

distinguished awards in his lifetime: The "Gizil Galam"

or Golden Pen (1986) and "Honored Journalist of the Republic"

(1989). after returning from seven years in a Siberian labor

camp (1955), Azer worked in publications and became Editor-in-Chief

of the Azerbaijan Telegraph Agency (Azertaj). Photo: Family of

Azer Alasgarov.

I hoped that Azer would

understand that the only reason I had divorced him was to continue

my education.

Another time when I was elected head of our Komsomol, someone

reported me, and the next day I lost the position simply because

my husband was an "Enemy of the People". It didn't

matter that we were already divorced. I was active, educated,

young and so full of enthusiasm to work and to create something.

But whenever I tried to do anything and move forward in my career,

the association with Azer always stood in the way.

There were many occasions when even my professors would pretend

not to see me. The same with students. But every time someone

didn't return my hello, it was a huge psychological blow to me.

I'll never forget one of my teachers - Ali Azeri - who taught

Persian. I was a good student and he liked me. A rather handsome

man and a bit elderly, he spoke with an Iranian accent. Once

I was passing him, and I lowered my head and didn't greet him,

afraid that he would ignore me like the other teachers did.

But he stopped me: "Aren't you Fatma?" he asked.

"Yes," I replied.

"Isn't your last name Khalilova?"

Again, "Yes."

"Didn't I teach you?"

"Yes."

"Then why don't you say 'hello' to your teacher?"

I couldn't hold back the tears. I confessed that I had been afraid

that he wouldn't acknowledge my hello, and that would leave me

so disappointed. He tried to console me by asking if I had seen

his new Persian language book. And then he took me to a nearby

bookstore and bought it for me and signed it. I have kept that

book to this day and treasure it so much.

Once I saw Bakhtiyar Vahabzade heading my direction [Vahabzade

is now one of Azerbaijan's distinguished poets]. He was a year

ahead of Azer and me at the university. Since he, too, was from

Shaki, we knew each other although we had never spoken. Azer

was the jealous type and didn't like when I talked with other

guys. I saw Bakhtiyar coming so I turned towards the window,

pretending to look outside. I thought that he would ignore me,

too, just like the others.

But Bakhtiyar approached and asked me if I knew why Azer had

been arrested. I lowered my head and didn't answer. Bakhtiyar

added: "He wanted freedom and independence for our country

- our Homeland. He fought for the independence of our mother

language." I didn't reply, but his words quieted my heart.

|

"It was such a

miserable period. Even brothers were afraid to share secrets

with each other. Fathers didn't trust their sons. Cousins didn't

trust one another. Those were the times we lived in. I don't

blame those people. They had no choice."

--Fatma Alasgarova

|

No Trust

Even Azer's cousins had to report that their relative had been

arrested by the NKVD. If they ignored the situation and someone

found out, they were afraid they would lose their Communist Party

privileges and be fired from work.

And another time, I was in Shaki and wrote my girlfriend in Baku.

She was a Party member. She got so scared that she took my letter

and showed it to one of the officials.

But looking back, I can't blame any of these people - Azer's

cousins, my girlfriend, my teachers, and the friends who didn't

return my hello. It was such a miserable period. Even brothers

were afraid to share secrets with each other. Fathers didn't

trust their sons. Cousins didn't trust one another. Those were

the times we lived in. I don't blame those people. They had no

choice.

Azer and I both suffered so much from this separation. Those

seven years were really difficult for both of us. If he had not

been arrested and sent into exile, we could have both done our

postgraduate studies together.

Released from Prison

Then, eventually, somehow they allowed him to return to Azerbaijan.

He was released in 1955 - seven years after his arrest. After

Stalin's death [1953], he wrote that he had been released from

labor camp three years early.

I was in Moscow trying to finish my dissertation and doing research

at the Lenin Library. There were quite a few Azerbaijani youth

studying there. We used to hang around with each other when we

were free.

After Azer was released in May 1955, they returned him first

to Moscow. Of course, I didn't know anything about it. But one

day, Afiga, one of my Azerbaijani girlfriends, saw him standing

in front of the Lenin Library. They spoke together and Afiga

told him that I, too, was in Moscow. She was so excited that

she forgot to tell him that I was actually inside the library.

She just said: "Fatma is here".

Azer didn't ask her exactly where, thinking that I would be at

Moscow State University. He spent half of the money that he had

earned while working in exile to hire a taxi to drive around

Moscow looking for me. He went to so many places. But all the

while, I was sitting there in the Lenin Library, engrossed in

my dissertation. When he couldn't find me, he took the train,

three days to Baku. When I learned that Azer had returned from

exile, I was stunned. Some of my friends told me to leave Moscow

and head to Baku right away to meet him. Some suggested that

I send a telegram of congratulations. But I decided to finish

my dissertation and then to head back to Baku in late July or

early August.

When I went back, I didn't go to visit Azer. I returned home

to my mother in Shaki. Since I had divorced Azer, I was afraid

that his mother would never accept me despite the fact that I

had discussed everything with my brother-in-law before filing

for the divorce. This had made him so sad. Tears had welled up

in his eyes. My aunt told him that I had to continue my education.

Marrying All Over Again

I remained in Shaki for a while before coming to Baku. One day

I was passing near the Scientific Research Institute where I

was doing my post-graduate degree. Azer's parents' house was

close by. Suddenly, I ran into Azer and his brother walking down

the street. We greeted each other. I welcomed him home. I can't

describe the contradiction of feelings I had churning inside

me. There we were in the middle of the street and I couldn't

hug him or anything. I felt like a stranger because I had divorced

him, and I was so afraid that he would feel the same way about

me. His brother wanted us to have the chance to talk together

and so he left us alone. Azer took me to their house. My mother

- in - law hugged me and cried. We all sat down and talked a

while. Everyone was all over both of us. Azer wanted to get away

from the crowd and talk to me privately, so he told everybody

that he was taking me out for a walk. And that was that. A couple

of days later, we went to register our marriage. We decided to

get married all over again.

At Kolyma

While in exile, Azer had been sent to the city of Magadan and

then on to Kolyma - remote camps with harsh winter climates in

northwestern Siberia near the Pacific. Azer used to say that

the prisoners were transported in train boxcars like sacks of

potatoes. Whenever he and other group members like his dear friend

Ismikhan spoke about their experiences in exile, it was so painful

to listen to what they had endured. They would talk about the

miserable conditions related to food and hard labor. Whenever

they did anything wrong, officials would beat them.

Azer said that he always tried to close his eyes to those things.

He worked very hard. He loved to read. Whenever he had free time,

he would read. They had a library there. When he came back, I

was amazed how knowledgeable he had become about the literary

classics of the world. He had read so many books in exile. He

used to read in the dark at night by candlelight. He would read

whatever he could find.

Nobody would hire Azer when he came back - not until he received

his rehabilitation papers [1956]. After many efforts, he started

working as a translator on a non-official basis. He still had

this big blot on his record - "Enemy of the People".

The day after he received his rehabilitation papers, he started

to work officially as a translator. Eventually, he was appointed

as Editor-in-Chief of the Azerbaijan Telegraph Agency (Azertaj).

Azer was very responsible about his work. He worked there for

more than 30 years and received the title of Honorary Journalist,

as well as the Golden Pen award (1986).

I can't say that I noticed much change in Azer's character after

he returned, except that everything put him on edge and made

him nervous. Before he was sent into exile, he was a very calm

and patient person. After he returned, he became so anxious about

everything. I suspect this is normal for someone who has lived

under such stressful conditions for seven years. But he always

knew how to control himself.

He still was a very social person. We used to attend concerts

and other social events in the city. Fortunately, he never got

ill upon his return.

In my opinion, Azer was a rather handsome man. I sensed that

some of the girls in our group were jealous because he had fallen

in love with me. Maybe they thought I wasn't pretty enough for

him. He had come from a poor family, but he always dressed neatly

and he was clean. He was smart and studied hard. And he was very

active. He was the head of the student union and used to help

students get shoes, clothes and food, especially during the difficult

war years.

As a husband, he was a family man. He was very respectful and

very loyal to our family and me. After Azer returned from exile,

we had one son - Farrokh - who was born in 1956. He's an artist

today.

No Regrets

Azer never regretted being a member of Ildirim. Never. A few

days before he died in 1995, he gave an interview to Voice of

America. They asked him that same question: "Did you ever

regret joining Ildirim?" He replied: "Absolutely not,

I have no regrets." He loved Azerbaijan and was proud of

having tried to do something for the Homeland and his mother

tongue.

Azer kept in touch with the other six members of Ildirim. They

often met, especially Ismikhan, Gulhusein and Aydin Vahidov.

He was especially close with Ismikhan Rahimov. In fact, we attended

Ismikhan's wedding when he married Zarifa.

Stalin's Legacy

What is Stalin's legacy as author of this terrible period of

repressions? Stalin was incredibly brutal. Our great, great writers,

art workers, actors, educated people were repressed. We lost

so many thinkers. So many intellectuals.

But Stalin won the Great War. Soldiers loved him for that. When

the commander said: "For Stalin! For our Homeland!"

the soldiers fought even harder. That's why many people still

hold Stalin in high regard today - despite the millions of lives

he destroyed.

But I can't help thinking that much of the responsibility for

all these evil things falls upon us. People betrayed one another.

If someone didn't like you, he would go and report you. The next

day you could be arrested. Betraying others is still part of

the psychology of our people today.

And what about Baghirov? Stalin and Mir Jafar Baghirov were very

close friends. My uncle always used to say: "If Baghirov

dies before Stalin, then Stalin will change Azerbaijan's name

to Jafarabad (city of Jafar). But if Stalin dies before Baghirov

does, then Baghirov will be crucified." And that's exactly

what happened.

And Baghirov? Well, in my opinion, Baghirov was a very honest

and serious person. I think he played a major role in Azerbaijan's

development. In his personal life, he was rather simple. We would

always see him in the same suit walking down the street with

his hands behind his back, and there was only one bodyguard following

him. We would greet him and he would return the greeting. But

everyone was scared of him. I think Baghirov in real life was

very different from the Baghirov in politics.

I had a friend who was Baghirov's niece. She used to tell us:

When Baghirov's son died, many people came to the funeral. He

told his relatives that his son wasn't different from any others

who had died, and that his funeral should not be any different

from his peers. Then he went to his room, laid face down on his

bed and cried bitterly. That's what they say.

On October 13, 1995, Bakhtiyar Vahabzade was celebrating his

70th Jubilee [Bakhtiyar was actually born on August 16, 1925].

He invited us to his party. Azer wasn't feeling well at the time

as he had diabetes but he didn't want to go to doctor. I told

him about Bakhtiyar's invitation and suggested that maybe we

shouldn't go.

But Azer said that if Bakhtiyar had invited us, then we had to

go. And so we went. We had a lot of fun that night at the party.

We met our old teachers from University and we shared a lot of

memories and laughed a lot. After the party, Azer felt very tired.

He told me that I had been right. Maybe it would have been better

if we hadn't gone. The next day Azer passed away.

There is saying that if you laugh a lot, something bad will happen.

But I'm glad that Azer spent his last day in good company and

enjoyed his time. When I die, I want to have my photo along with

Azer's on my gravestone. I want everyone to know that I was the

wife of such a great person. He was a man who stood up for what

he believed, despite tremendous cost. I'm so proud to have been

his wife.

Fatma Alasgarova has been teaching

at the Pedagogical Department of Baku State University since

1962 where she is a docent there. She was interviewed by Aysel

Mustafayeva in November 2005.

Back to Index AI 13.4 (Winter

2005)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|