|

Spring 2004 (12.1)

Pages

36-39

Kamal Talibzade

My Father

Abdulla Shaig

Portrait by his son,

Kamal Talibzade

It's

so difficult to write about your father and the impact he has

had on your life. Though my father Abdulla Shaig passed away

nearly 45 years ago, he is still so vivid to me - both in my

conscious thoughts as well as my subconscious dreams. He speaks

to me, offers advice and even admonishes me. Every day when I

go to work, I pass by the Cemetery of Honored Ones [Fakhri Khiyaban]

where he is buried and pray for his soul and for the souls of

our other great artists. It's

so difficult to write about your father and the impact he has

had on your life. Though my father Abdulla Shaig passed away

nearly 45 years ago, he is still so vivid to me - both in my

conscious thoughts as well as my subconscious dreams. He speaks

to me, offers advice and even admonishes me. Every day when I

go to work, I pass by the Cemetery of Honored Ones [Fakhri Khiyaban]

where he is buried and pray for his soul and for the souls of

our other great artists.

Abdulla Talibzade was born on February 24, 1881, in Tiflis (now

Tbilisi, Georgia); he died in Baku on July 24, 1959. We originally

came from Borchali (now Marneuli) in Georgia. This region is

known for having the greatest concentration of Azerbaijanis.

Today family members of my uncles' generation still live in Borchali.

I was able to visit the house in Tbilisi where my father was

born and grew up, as well as to visit the village Sarvan where

we trace our native roots. My grandfather, Mustafa Talibzade,

was an "akhund" [a clergy of rank in Islam] in Sarvan

and later moved to the capitol Tbilisi.

Pen Name

My father soon adopted a pen name - Shaig. It is derived from

Arabic and Persian-the root, "Shovq", meaning "Light".

Its literally meaning relates to "Love".

He began his career as an educator. In fact, in 1918 after Azerbaijan

Democratic Government was established, my father was the first

person to succeed in opening a secondary school in the Azeri

language.

My father is often associated with children's stories and drama,

but the truth is that many of his works are related to the political

and economic conditions of his times.

We keep his handwritten manuscripts in our museum - the Abdulla

Shaig Home Museum1. This past year- 2003 - I was finally

able to publish some of his works in a book entitled, "Arazdan

Turana" [From Araz to Turan. Araz, referring to the river

that separates Azerbaijan from Iran and Turan, identifying the

expansive region where Turkic nations live].

In this book, we included one of my father's poems that he had

written during Stalin's Repression. [See "To the Enemy of

the Nation" by Abdulla Shaig in this issue]. Still there

are a number of works that we have yet to publish.

Below: Shaig's son Kamal Talibzade in his

father's home museum. Photo by Blair, 2004.

Hidden Manuscripts Hidden Manuscripts

It's quite amazing how I found these poems. One day, after my

father had died in 1959, I was looking through my father's bookcase.

Suddenly, I came upon something thin wrapped up in a newspaper

tucked away in a drawer at the bottom of the bookcase. I opened

it and discovered my father's handwriting [Azeri in the Arabic

script2].

These were poems exposing Stalin's despotism, Mirjafar Baghirov's3

tyranny, and other poems dedicated to the literary people who

were killed during those years of Stalin's Repression [mostly

in late 1930s]4.

What could I do with such material? It was so dangerous to have

them in my possession as only a few years had passed since Stalin's

death in 1953. So I carefully wrapped the works and took them

to my apartment and hid them in the floorboards. They stayed

there until Azerbaijan gained its independence in late 1991.

Finally, these days we are gradually beginning to publish some

of this material.

Many of our political problems originate from the fact that my

Uncle Yusif Ziya was one of the famous generals of his time.

He lived in Turkey for many years. After the Soviet government

was established in Azerbaijan in 1920, Nariman Narimanov, as

the top official in Soviet Azerbaijan, invited Zia to come back

to Baku because Narimanov's family and Shaig's family had been

neighbors from childhood in Tbilisi.

So, in 1920 my uncle returned with his family to Baku. With Narimanov's

help, Lenin appointed him as the Minister of Foreign and Military

Affairs in Nakhchivan5. But in the end, he decided not to

take the position. My uncle understood that he wouldn't be able

to realize his own principles within the Soviet Government. He

heard that Anvar Pasha - a great Turkish military leader was

fighting against the Russian Bolsheviks in Central Asia so he

went there and joined him. Both Pasha and Zia died during battles

in Turkmenistan in 1921.

Political Repercussions

Once I was taking part in a plenary session of the Writers' Union

during the Great Patriotic War [World War II]. One of the writers

during his speech pointed at me and said: "Look at Kamal

Talibazde! His Uncle Yusif Ziya along with Mammad Amin Rasulzade6

now sit next to Hitler and they're trying to establish an Azerbaijani

division, while his nephew sits among us."

At that time, there were rumors circulating that Yusif Ziya was

still alive and that once he and Rasulzade had approached Hitler

in an attempt to create an Azerbaijani legion within the fascist

German army.

Such pressures and threats often took place. They had one single

aim - to cast doubt upon Shaig's family as he was a relative

of the poet Samad Vurghun (1906-1956) [See this issue]. This

campaign lasted well into the 1950s, even after Stalin's death.

Once my sister's friend Shukufa Ismayilova came running to us

with the news that her uncle along with Husein Javid7 had

returned from their exile in Siberia and that they were waiting

for us at the Bilajari Station. Rumor had it that they were clothed

only in rags in the bitter cold weather. My father and Husein

Javid had been close friends.

Left: Abdulla Shaig, famous poet, children's writer

and educator. Shaig's poems that were critical of Stalin's regime

are now finally being published by his son now that Soviet Union

no longer exists. Courtesy: Abdulla Shaig Home Museum Left: Abdulla Shaig, famous poet, children's writer

and educator. Shaig's poems that were critical of Stalin's regime

are now finally being published by his son now that Soviet Union

no longer exists. Courtesy: Abdulla Shaig Home Museum

Prior to his arrest Javid used to visit us, Father would send

me off to buy wine, as Javid loved wine. So, not knowing anything

about Javid's whereabouts since his arrest, my Mother organized

a bundle of warm clothes and gave it to my sister to take to

Javid's wife - Mushgunaz khanim. Father was bedridden at the

time with an ulcer. Javid's wife did go to the train station

to wait for the return of her husband. She waited such a long

time and, of course, nothing happened. Javid did not come. How

could we have known that this great writer's body lay in distant

Irkutsk in an anonymous grave identified only by a number8?

Later Mirjafar Baghirov's was informed about this event and mentioned

it in one of the plenary sessions of the Central Committee of

the Azerbaijan Communist Party. He said: "Hey people, do

you know what Mirza9 has done? We convinced him that Husein

Javid had returned to Baku, and Mirza went out to meet him and,

in the process, got his suitcase stolen."

What suitcase? That was a lie. How could my bedridden father

go to Bilajari station? One of my father's students, who was

present in that session, informed us about this speech.

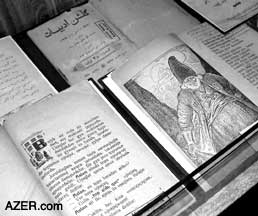

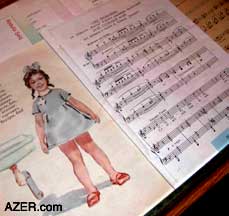

Above: from left to right: 1. Entrance to

Abdulla Shaig's Home Museum in Baku at 21 Abdulla Shaig Street.

Third Floor. 2. Exhibits in the Shaig Home Museum. Children's

books by Shaig. Note the examples of Azeri in the Arabic as well

as the early Latin script which was used in the 1920s and 1930s

before Cyrillic was imposed by Stalin. 3. Some of Shaig's lyrics

put to music for children. Photos are by Blair, 2004

In short, my father

was fired. His name was removed from children's textbooks. Naturally,

this affected me as well. At the university, the Communist Party

Committee called me in and criticized me: "Why didn't you

bring up your father better?" Merely associating with someone

who was branded as an "Enemy of the People" could result

in death.

Then a summons came for my father. He was asked to go to the

KGB House down by the seaside. Everyone knew what such a summons

meant. Later we learned that Yemelyanov and Mirteymur Yagubov

(my father's former students) seriously criticized my father

but then they released him.

I went to meet my father. I was so worried. He saw me from a

distance and smiled: "Don't be afraid. They've released

me," he said.

In the end, Abdulla Shaig escaped repression due to his students,

my father's two most favorite students - Ruhulla Akhundov and

Taghi Shahbazi Simurg. In 1932 they already realized that it

would be dangerous for my father to remain in Baku so they assigned

him to work at the Teacher's Training College in Shusha. My father

taught there six years while our family remained in Baku. I was

eight years old at the time. Unfortunately, the students who

saved his life were themselves killed by Stalin's repressive

policies.

Character

Let me share some things about my father's character. Even my

father's attitude towards objects around him provides a glimpse

of his spirit. Abdulla Shaig had a writing table that he had

bought in 1906. One day my mother - Shahzade khanim - got the

idea that she should replace the furniture, including the writing

table. She always liked order in the house.

"Abdulla," she said, they've brought some modern writing

tables. Let's change yours and buy a new one." It was very

difficult for my father to go against her will, as she was a

kind and noble person. He always got immense satisfaction from

trying to fulfill her desires. But this time he didn't say anything.

The next day he wrote a poem, entitled, "My Table"

and read it to all of us and that solved his dilemma. Could he

part with his friend of more than 40 years? Was it in his character

to be unfaithful to this table, which had witnessed his sleepless

nights, his grief, his happiness?

Here's how Father wrote about his devoted friend - his writing

table: "The love of art didn't stop in my heart. My greatest

goal is to create new works along with you with the power I get

from my surroundings, the strength I get from my love. It's been

40 years now that we've been working together. Probably I'll

write my last work on you."

And, it was that same writing table, now included in the exhibits

at the Abdulla Shaig Home Museum, upon which he did write his

last work. The table remains in its original position - in a

corner of his study. Now sometimes, his own grandson, his namesake

- little Shaig - sits at that writing table and looks through

his colorful books and senses that the world is both a marvelous,

but strange, place. Little Shaig bears such an uncanny resemblance

to his grandfather, especially in the way that he sits and conducts

himself. It's as if Shaig has not passed away.

Shaig was faithful to everybody, everything, even to his personal

belongings. His devotion to his Motherland and nation was connected

to that aspect of his character.

My mother was Abdulla Shaig's second wife. His first wife Raziyya

khanim had died in 1919 of illness. Later he married my mother.

Actually, my father married quite late in life. He had traveled

quite a bit when he was young, visiting a number of cities in

Russia. It seems that he wasn't that interested in settling down

so he married rather late.

I was the oldest child in the family. I was born in 1924. (An

older sister Altunsach, born in 1921, died when she was still

a baby). I remember my father treating me as an adult ever since

childhood. He did not withhold family secrets from me. We were

especially close during the last 15-20 years of his life. We

would often sit and talk. He would share his thoughts, dreams,

and plans and sometimes recount his memories and his adventures

of youth. He used to ask me questions and even argue with me

- always with the intent of trying to learn something new from

me.

In those last years, when I would return from work home at lunch,

I would find him in bed, resting. He wouldn't sleep but would

wait for me and say, "Let's see what news Kamal will bring."

After eating, I would lie down next to him. He would move over

a little in order to make some space for me. He would put his

slim arm under my head and remain silent for a while, as if trying

to drink in the happiness of the moment. Then he would ask: "What's

news?"

He was especially interested in the developments that were taking

place in the press and in the arts. He would pass on to me some

of the things he had read or heard himself. Towards the end of

his life, he developed a keen interest in newspapers such as

Izvestiya, Kirpi (Hedgehog), Krokodil (Crocodile), and Baki (Baku).

I began to realize that he was getting older. This writer, educator

and thinker who used to stay up working tirelessly until 2 to

4 o'clock in the morning even after working all day, began to

lag in energy and read less.

Old Age

Shaig got so bored with old age. He was always longing for new

things, trying to be conscious of everything going on around

him, especially as it related to the media. He suffered from

not being able to keep up with his times. But he didn't give

way to despair. That was his character; he was an optimist by

nature. He lived his entire life with the hope of tomorrow.

I've spoken so often about my father in many different venues.

I've heard so many anecdotes about him, read articles and listened

to poems. Always, the main focus centers on his personality.

Of course, people talked about him as a poet, publisher, teacher

and public person, but they preferred to focus on his personal

features. Some people thought he even looked like an angel or

a prophet.

Actually, my father was an ordinary and very simple man; even

his simplicity sometimes seemed naive. He was a kid with children,

and an adult with the older folk. He could meet people on various

levels and professions, talk to them at length, and find a topic

for conversation to explore together with them. It was if he

had a spiritual need for such communication.

In addition to his simplicity, my father was very kind, well-mannered,

calm, careful, patient and restrained. It's hard to find anyone

who can remember when he got nervous and angry, or when he said

a rude word to someone. Samad Vurghun, one of our relatives,

who often stopped by to see us loved to tease my mother: "Sister-in-law,

tell me the truth, has Mirza ever gotten angry with you? One

can't believe that a person never gets angry sometimes."

My mother would reply: "Samad, I really can never remember

such a situation." Later our neighbors sometimes referred

to my father as their "Drop of Valerian10".

My father had the ability to influence other people's behavior

through his kindness. He would behave in such a way that it was

impossible not to fulfill his smallest desire.

I remember how he used to gather us children around him. There

were three of us: me, my sister Gulbaniz, and our brother Ildirim.

Father would tell us stories and anecdotes. He would recite poetry

by heart that he knew in Russian and Persian. He would create

tales that were filled with kind, well mannered, and well behaved

creatures.

All of these qualities stemmed from my father's love for humanity.

These characteristics, in turn, manifest themselves in his advocacy

for democracy and humanism in his work. You can sense it in his

works.

End Notes:

1

The Shaig Home Museum is located at 21 Abdulla Shaig Street in

downtown Baku. It is open to the public. Tel: (994-12) 92-29-61.

2

The Arabic script was used for writing Azeri prior to the mid-1920s.

Azerbaijan changed its alphabet three times during the 20th century

- from Arabic, to modified Latin, to Cyrillic and back to modified

Latin again. For more about alphabet changes, see the entire

issue: Alphabet and Language in Transition, AI 8.1 (Spring 2000).

Search Alphabet at AZER.com

3

Mirjafar Baghirov was Secretary General of the Central Committee

of Azerbaijan Communist Party during Stalin's regime, and blamed

for the terror that was carried out in Azerbaijan when tens of

thousands of people, including many intellectuals, were exiled,

imprisoned and executed.

4

For list of names of the 25 writers who lost their lives during

Stalin's repressive years, see photo of the plaque in the Writer's

Union in Baku. See AI 7.1 (Spring 1999), p 67. Search at AZER.com.

5

Nakhchivan is the non-contiguous part of Azerbaijan in the southwest,

separated from the mainland Azerbaijan by Yerevan by about 40

kilometers.

6

Mammad Amin Rasulzade was the Founder of the first Azerbaijan

Democratic Government in 1918. In other words, he was one of

the most vocal opponents of the Bolshevik government that became

established in Azerbaijan in April 1920. For more details about

what happened to Rasulzade when he fled the country after the

Bolsheviks came, see "Mammad Amin Rasulzade: Founding Father

of the First Republic," by his grandson Rais Rasulzade in

AI 7.3 (Autumn 1999) pp 22-23. Search at AZER.com.

7

Husein Javid (1882-1944) was a dramatist and poet who was arrested

on June 4, 1937, the year at the height of Stalin's repression

and exiled to Siberia. Javid was sentenced to eight years in

prison, but he died within 7 years. Many of his unpublished manuscripts

were confiscated. No one knows their contents. See "Javid:

The Night Father was Arrested" by his daughter, Turan Javid

in Azerbaijan International, Spring 1996, page 24. Search at

AZER.com.

8

On October 29, 1996, President Heydar Aliyev dedicated a mausoleum

in Nakhchivan to the memory of Husein Javid. The crypt contains

the graves of Javid, his wife and son. His daughter Turan was

present for the commemoration. See AI 4.4, (winter 1996), p 37.

In Baku, a sculpture by Omar Eldarov dedicated to the works of

Javid stands in front of the Academy of Sciences. [See AI 2.2

(Summer 1994), pp34-36. Search at AZER.com.

9

Mirza is a title for a man who was perceived to be an intellectual

and very literate.

10

Valerian is an herb that produces a calming effect on the heart.

In Azerbaijan, it is available in liquid form.

More Works:

(1) "Transitions:

Literary Criticism in Azerbaijan - A Look at Soviet Works"

by Kamal Talibzade, AI 4.1 (Spring 1996), pp 28-29.

(2) "An

Eyewitness Account: Learning to Read All Over Again - Alphabet

Changes in Azerbaijan Throughout the Century" by Kamal Talibzade,

AI 8.1 (Spring 2000) pp. 64-66.

Works by Abdulla Shaig have

also been published in Azerbaijan International: Search at AZER.com

(1) "The

Cheating Fox: Kid's Story Warns Children to Watch Out"

(Fox Goes on Pilgrimage by Abdulla Shaig) AI 6.1 (Spring 1998)

pp 70-71.

(2) "Undelivered

Letter" by Abdulla Shaig, AI 7.1 (Spring 1999), pp 22-23.

Back to Index

AI 12.1 (Spring 2004)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|