|

Autumn 2001 (9.3)

Pages

64-67

Secrets - No

More

Discovering

Who My Great Grandparents Were

by

Gulnar Aydamirova

Beginning with the Red

Army's takeover of Baku in 1920 and continuing through Stalin's

brutal Repressions of the 1930s, Azerbaijanis endured a great

deal of suffering at the hands of early Soviet leaders. Yet,

later generations wholeheartedly accepted the Communist system,

even though many of their older relatives had been arrested and

exiled or executed. Beginning with the Red

Army's takeover of Baku in 1920 and continuing through Stalin's

brutal Repressions of the 1930s, Azerbaijanis endured a great

deal of suffering at the hands of early Soviet leaders. Yet,

later generations wholeheartedly accepted the Communist system,

even though many of their older relatives had been arrested and

exiled or executed.

Soviet children were reared to honor Lenin and have faith in

Communist ideology. It wasn't until the Black January massacre

of 1990 that many Azerbaijanis completely turned their backs

on the Soviet system. Many of them burned their Communist Party

membership cards in protest even though they had worked their

entire lives to get them.

I think we Azerbaijanis forget

things easily. On the one hand, this is probably a good trait

- we don't seem to be able to harbor hatred in our hearts very

long. But it also means we tend to forget things that should

never be forgotten.

Gulnar Aydamirova, 18, belongs to the generation of Azerbaijani

young people that is barely old enough to remember the collapse

of the Soviet Union. She was only eight years old in 1991, when

Azerbaijan became independent. Recently, she has been digging

into her family background to learn more about two of her great-grandfathers

who were executed by Soviet leaders and labeled as "Nation's

Enemies". She found that her family initially resisted the

Soviet system and endured severe consequences. Hers is a story

that could be told by many other Azerbaijanis.

When I was a

child, I used to say that I had five grandfathers: Allah baba

(God), my own two grandfathers, plus Shakhta baba (Santa Claus;

literally, Grandfather Frost). Though it's hard to believe now,

I always added Lenin baba (Grandfather Lenin) to my list as well.

Below:

Gulnar Aydamirova,

almost 7, in school uniform, proudly wearing her Octobrist star

with the portrait of Lenin as a young boy. Becoming an Octobrist

(referring to the October Revolution of 1917) was the first of

several steps up the ladder to becoming a Communist Party Member

in adulthood. Photo: 1989.

I don't know why I loved

Lenin so much; maybe it was because the ideology was so strong

back then. Lenin was considered the grandfather of all Soviet

children. I don't know why I loved

Lenin so much; maybe it was because the ideology was so strong

back then. Lenin was considered the grandfather of all Soviet

children.

I remember that I even had a picture book about his life. It

was my favorite book. My mom gave it to me when I was six. I

had just started first grade. The book told about Lenin's life,

mostly about his family and childhood. One picture showed him

surrounded by many children. This was meant to show that he was

a friend of every Soviet child. The book said that he had been

an excellent student and had studied hard and gone to school

half an hour early each day. No doubt there was a lesson there

that we were supposed to learn.

When I was in kindergarten, my class visited Lenin's Museum in

the heart of Baku. We were all very excited to go there. Actually,

I don't really remember much about the museum itself except that

there were a lot of pictures of Lenin standing in the midst of

many people. He was holding his cap in his hand. Even though

I don't remember the details, it still made an impression on

my young mind.

Today the museum building still exists, but the Lenin memorabilia

is gone and in its place is a large exhibition of carpets from

all the regions of Azerbaijan. Who knows where all that stuff

related to Lenin is now?

When I was seven years old, I became an "Oktobrist",

which refers to the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia,

when the Soviets came to power. As an Oktobrist, I used to wear

a little pin in the shape of a star. There was a portrait of

Lenin as a young boy on it. For kids in Grades 1-4, it was the

initial step up the ladder to becoming a member of the Communist

Party. After that, I was supposed to become a Pioneer, and then

a Komsomol.

The Soviet Union collapsed when I was eight years old, so I never

did become a Pioneer or a Komsomol.

Today, less than a decade later, it seems that many young children

in Azerbaijan don't even know who Lenin was. My sister is nine

year old and in the fourth grade. She was born in 1992, only

a year after Azerbaijan became independent. When I asked her

and a 12-year-old neighbor boy who Lenin was, my sister thought

for a moment, but the only thing she could tell me was that he

was Russian. Her friend said that Lenin was the president.

Below:

The Afandi

Family. Zabishah Afandi (my grandmother's brother who was executed

because of his father) is the third from the left on the second

row. The elderly woman next to him is Khanim baji, the mother

of my great-grandfather (Hamdulla Afandi's) mother. His wife,

my great-grandmother (Nurjahan Afandizade), is the second from

the left on the third row. The little girl she is holding is

my grandmother, Zihajja Aliyeva. Others include my great-grandfather's

other wives, children and nephews. This photo was taken before

Stalin sent my family into exile in 1926. My great grandfather

Hamdulla Afandi, who was a member of the Azerbaijan Democratic

Parliament (1918-1920) and later executed in 1926, is not pictured

here. Photo is from around 1925.

When I was her age,

I knew a lot about Lenin. At least I knew what we had been taught

at school. But at the same time, it's only been since independence

that I've begun to realize how many problems Lenin and other

Soviet leaders caused my family. When I was her age,

I knew a lot about Lenin. At least I knew what we had been taught

at school. But at the same time, it's only been since independence

that I've begun to realize how many problems Lenin and other

Soviet leaders caused my family.

Digging in the

Past

I'm not sure when I first started hearing stories from my mother

about my family's history; it seems like a long time ago. But

lately, I've been digging into my background more systematically.

I've been talking to my grandparents on my mother's side, both

78 years old now. They were both eager to share their stories.

I've always known that one of my great-grandfathers was executed

for being an "Enemy of the Nation", but there were

so many other things that I didn't know. For example, I didn't

know that he had been a Member of Parliament in the Azerbaijan

Democratic Republic (ADR) (1918-1920). Nor did I know how difficult

life had been for my grandfather's family after he was executed.

I also didn't know that my grandmother's stepbrother had been

killed.

My great-grandfather Hamdulla Afandi Afandizade (killed in 1926)

was a bey (landowner) in the Galagah village of the Davachi region,

in northeast Azerbaijan. Relatively well off, he lived in a rather

large house with his four wives and 14 children. (Wealthy men

back then often had more than one wife.) The Afandi family had

been respected in the region for quite a long time.

My great-grandfather lived during turbulent times. In the spring

of 1920, when the 11th Red Army was moving from Yalama (in northeastern

Azerbaijan, bordering Dagestan) to Baku, my great-grandfather

gathered people from the Guba and Davachi regions to fight against

the troops. Through their efforts, they were able to head off

the train that was moving troops to Baku. But of course, they

couldn't resist long against such a large army. They somehow

succeeded in delaying the train by a few days - at least, that's the way my grandparents

tell it.

Below:

My great

grandfather Ali Aliyev, a mullah, was killed in 1937 at the height

of Stalin's Repressions.

My great-grandfather's

brave efforts to protect Azerbaijan soon caught up with him.

In 1926 he was arrested and never heard from again. The Bolshevik

leaders called him an "Enemy of the Nation" and then

executed him. His body has never been returned to his family.

Nobody really knows what happened to him. My great-grandfather's

brave efforts to protect Azerbaijan soon caught up with him.

In 1926 he was arrested and never heard from again. The Bolshevik

leaders called him an "Enemy of the Nation" and then

executed him. His body has never been returned to his family.

Nobody really knows what happened to him.

More Troubles

But that wasn't the end of troubles for my family. Their house

and belongings were confiscated. My great-grandfather's wives

managed to hold on to some of their jewelry, but it was nothing

compared to what they had once owned. They passed some of their

belongings to people in the village for safekeeping. But they

never got anything back.

Then his family and all of his relatives were exiled to Nakhchivan,

the non-contiguous part of Azerbaijan bordering Turkey, separated

from mainland Azerbaijan by a strip of Armenia. Then they went

to Gazakh, the northwest corner of Azerbaijan bordering Georgia.

My grandmother's older stepbrother Zabishah Afandizade was a

teacher. One day he told his stepmother that some people had

been asking about him. He knew that they were going to come and

take him away, and he didn't want it to happen while his children

were watching. My great-grandmother suggested that he stay at

her house. But he decided against it as he didn't want to leave

his own children alone.

Just as he had predicted, they arrested him and took him to prison

the very next day. His crime? He just happened to be the son

of an "Enemy of the Nation." The next day, my great-grandmother

and grandmother went to visit him in prison and take some food,

even though it was very risky to do so. The following day, they

went again, but the prison guards told them that he had already

been shot. That was 1937, during the height of Stalin's Repression.

Tens of thousands of people disappeared during those days.

Above: My brother, Nariman

Aydamirov, loved dressing up in uniforms that were worn during

the Soviet period. This photo was taken at age 5 in kindergarten,

in December 1990. Above: My brother, Nariman

Aydamirov, loved dressing up in uniforms that were worn during

the Soviet period. This photo was taken at age 5 in kindergarten,

in December 1990.

My grandmother's

family continued living with this curse up until Stalin's death

(1953) and the subsequent trial of Mir Jafar Baghirov in 1954.

Since one of their family members had been declared an "Enemy

of the Nation" who had opposed the Soviets, the family encountered

difficulties everywhere they turned. They even tried changing

their last name from Afandizade to Ismayilov, just so people

wouldn't know that they were related to such a family (Ismayil

happened to be the name of Hamdulla Afandi's father).

My grandmother's older brother had received an assignment to

teach in Davachi, the region that they were from. But it didn't

work out because the people there were always pointing at him.

So he had to request a different teaching assignment in Khudat,

where no one knew who he was.

Religious Persecution

Another one of my great-grandfathers, Ali Aliyev (killed in 1937),

was also a victim of the Soviet regime because he was a mullah,

a religious man. People used to call him Mullah Ali. He lived

in Galaghan village.

Mullah Ali was known as a very kind man who always helped needy

people. My great-grandmother used to say that she had never washed

two pairs of pants for him at the same time, meaning that if

he ever had an extra pair, he always gave them to someone else

who needed them.

When the Soviets took power, they began killing the mullahs,

burning mosques and destroying everything that was written in

Arabic script [At that time, the Azeri language was written in

Arabic script]. My great-grandfather knew that he, too, would

be targeted, so he decided to leave the area. From 1930 to 1937

he lived here and there, mostly hiding out in the southern regions

of the country. He would sometimes come back at night to visit

his wife and three sons. Mullah Ali would never stay long and

always left before dawn.

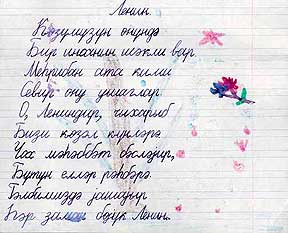

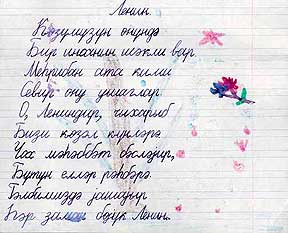

Lenin Lenin

Left:

Gulnar's

poem at age 7 (1990) to her uncle, which she copied from a school

book featuring Lenin. Gulnar used to call Lenin one of her "Baba's"

(grandfathers).

There's a picture of one person

in front of our eyes.

Kids love him as a kind father.

He is Lenin, he has taken us to beautiful days.

All the nations love the leader deeply.

Great Lenin always lives in our hearts.

He was a close friend of every nation and every country.

His youngest

son (my mother's uncle) doesn't even remember his father, as

he was very young at the time. But he does remember a dream that

he had, in which he woke up and found that a man was holding

him. He says he recalls how the man kissed him on the forehead.

He remembers the man's face vividly and has never forgotten it.

Perhaps the memory dates from one of those nights when Mullah

Ali came to visit his family.

My grandfather recalls one night when his father came back for

a brief visit. When he was leaving, a neighbor spotted him and

ran to tell on him to the village authorities. Back then, some

people used to spy on their neighbors to gain favor with authorities

in the Soviet system. You couldn't trust anyone.

But by the time the neighbor returned with several men, my great-grandfather

had disappeared. They asked my grandmother where he had gone.

She was young and alone, with her three young sons. She snapped

back at the neighbor: "What kind of person are you? Didn't

you just see him off yourself, and now you come and ask me where

he is?" Of course, later the neighbor had some explaining

to do.

My great-grandmother grew to hate the Soviet system. But she

never spoke about it much as she was very afraid. My mother recalls

that she used to warn them that "even walls have ears"

[now a traditional Azeri saying].

Mullah Ali owned a lot of books that were written in the Arabic

script. He used to say that each one of them had the value of

a bull calf. Since the Soviets tried to eradicate everything

associated with Islam, including secular books written in this

script, his family knew their house would be searched. They asked

many people to keep the books, but no one would. Finally, they

tossed the precious books into the river. He remembers watching

them float by in the water.

No one saw or heard from my great-grandfather after 1937. He

just disappeared. Later, someone said that he had seen him at

a certain place. People went looking for him, but no one found

him. My great-grandmother believed that if he had really been

alive, he would have come and visited them, no matter how great

the risk. But he never came.

From then on, my grandfather's family also became targeted as

a family of an "Enemy of the Nation." His sons had

difficulty pursuing their studies. For instance, when my grandfather

and a neighbor friend went to the nearby town of Guba to take

the entrance exam for technical secondary school to become teachers,

they were told to leave the classroom. They were singled out

because of their fathers. Another teacher, who was sympathetic

to their situation, invited them to return to the classroom.

The next day, that teacher disappeared. It turns out, the authorities

had been watching him for some time.

My grandfather and his brothers weren't allowed to become members

of the Communist Party. Of course, they never really wanted to.

At the time, though, it was important to be a Party member. The

youngest son -

the one who had never remembered seeing his father - eventually did become

a Party member.

Revolutionaries

Surprisingly, I also discovered that I had a few famous Communist

revolutionaries in my family: Gazanfar Musabeyov (1888-1938)

and Ayna Sultanova (1895-1938). This brother and sister were

cousins to my great-grandfather Hamdulla Afandi.

The two of them worked hard to establish Soviet rule in Azerbaijan.

They say that Gazanfar met with Lenin on several occasions and

passed him information about the situation in Azerbaijan. He

served as head of the Republic's People's Commissars' Union from

1922 to 1929, then became a leader of the Caucasian Federation's

Central Revolutionary Committee. From 1931 to 1937, he was the

head of the Caucasian Federation's People's Commissars' Union.

His sister Ayna organized the Women's Section of the Azerbaijan

Communist Party's Central Committee. She also served as the first

editor of "Eastern Woman" (Sherq Qadini) magazine,

which later became "Azerbaijani Woman" (Azerbaycan

Qadini). She held other high positions including Commissar of

the Azerbaijan Educational Commissariat, head of the Culture

department of the Caucasian Federation's Trade Union Council

and head of the women's department in the Caucasian Country Committee.

Even though these two held high positions in the Communist Party,

they enjoyed no immunity from the terror of that system. In 1938,

during Stalin's Repression, they were both denounced as "Enemies

of the Nation" and executed. Ayna's husband, Hamid Sultanov,

was killed that year as well. All of a sudden, the Soviet system

didn't seem to need them anymore. Maybe they knew too many of

the Party's secrets and were seen as a threat.

Mother's Generation

By the time my mother was growing up in the 1960s, the family's

situation had changed considerably; it was almost like a complete

reversal. By that time, most of the stigma of being related to

an "Enemy of the Nation" had disappeared. Nearly a

decade had passed since Stalin's death, and the Repressions were

over. Krushchev's era was known as a "thawing" period

when more freedom was given. It was a swing of the pendulum to

try to counter some of the harshness of Stalin's era.

When Mom was growing up, she became an Oktobrist, then a Pioneer,

and eventually a Komsomol. She says that the Communist ideology

and propaganda was so strong at the time that she really believed

in it.

"It was an honor to become a Pioneer," she told me.

"Everyone aspired to be one. I remember that we had to answer

several questions before we were accepted to be Pioneers. It

would have been embarrassing and shameful not to become one."

As a teenager, she took the next step by becoming a Komsomol.

"I worried so much about taking the exam," my mother

told me. "We were asked a lot of questions about the history

of the Communist Party and its Congresses. It was a big deal,

and there was a special acceptance ceremony."

It seems strange to me that after all that my family had suffered,

my mother and her generation didn't hate the Soviet system. When

I asked her about this, she said that her parents had not taught

them to hate the system. It seems they must not have wanted their

children to suffer as they had. Of course, they knew that if

their children said anything negative about the government to

their friends or at school, the whole family could be jeopardized

again. It was for this reason that children weren't taught the

whole truth. Looking back, you have to give the parents credit

for succeeding in just keeping their families alive.

I think we Azerbaijanis forget things easily. On the one hand,

this is probably a good trait - we don't seem to be able to harbor hatred in

our hearts very long. But on the other hand, we tend to forget

things that should never be forgotten.

Now that I've learned more about my family, I have a newfound

sense of respect for my ancestors. I'm sorry that I never knew

them personally. They believed in the independence of our country.

They wanted freedom. They only lived through two years of independence

(1918-1920), but they believed in it so much that they fought

to protect it. My family tree is full of individuals who suffered

as "Enemies of the Nation" - but to me, I can at last look at them

from a perspective that makes me respect them as great heroes.

Gulnar Aydamirova

(1983- ) was selected as a foreign high school exchange student

in Colorado (school year 1999-2000) in a program sponsored by

the U.S. Freedom Support Act. She joined the editorial staff

at Azerbaijan International magazine and is currently pursuing

a bachelor's degree in Linguistics at the University of Languages

in Baku.

____

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.3) Autumn 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.3 (Autumn 2001)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|