|

Winter 2000 (8.4)

Pages

18-19

The

Kish Church The

Kish Church

Digging

Up History

Norwegians Help Restore

Ancient Church

An interview

with J. Bjornar Storfjell

Other

articles by or related to Bjornar Storfjell:

Thor

Heyerdahl's Final Projects - Bjornar Storfjell (AI 10.2,

Summer 2002)

Voices

of the Ancients: Rare Caucasus Albanian Text - Zaza Alexidze

(AI 10.2, Summer 2002)

Church

in Kish: Carbon Dating Reveals Its True Age - Bjornar Storfjell

(AI 11.1, Spring 2003)

Who would

have guessed that a rather plain, small church, found in a remote

part of northwest Azerbaijan, would excite so much international

attention? What could be so fascinating about a building that

hasn't even been in use for the past two centuries?

Norwegians have the answer. In the village of Kish, near the

town of Shaki, which snuggles up to the foothills of the Caucasus

mountains, a team of Azerbaijani and Norwegian scholars is investigating

a remarkable remnant of Caucasus Albanian Christianity. Based

on their findings, they estimate that this local church may be

nearly 1,500 years old.

How did the Norwegians even hear about the church? Some of the

credit goes to Eyvind Skeie, a well-known Norwegian author and

scriptwriter who has been involved in various cultural projects

involving Norway and Azerbaijan. Skeie made a video of the church

in Kish, which appeared on the TV news in Norway in December

1998 as a short, interesting religious feature for the first

day of Christmas. The piece mentioned that this was an ancient

church and that they were eager for scientists to explore and

excavate it though, at present, there was no funding for such

a project.

Norwegian-American archeologist

J. Bjornar Storfjell chanced to hear the announcement, even though

he wasn't paying much attention to the television playing in

the background. It sparked his interest, since he has done a

considerable amount of research on the Byzantine period and early

churches in Jordan, Israel and the Middle East. Storfjell sent

an e-mail to the Norwegian Broadcasting Company, which put him

into contact with Skeie. What followed was a full-scale excavation

that began in the summer of 2000 in Azerbaijan. Norwegian-American archeologist

J. Bjornar Storfjell chanced to hear the announcement, even though

he wasn't paying much attention to the television playing in

the background. It sparked his interest, since he has done a

considerable amount of research on the Byzantine period and early

churches in Jordan, Israel and the Middle East. Storfjell sent

an e-mail to the Norwegian Broadcasting Company, which put him

into contact with Skeie. What followed was a full-scale excavation

that began in the summer of 2000 in Azerbaijan.

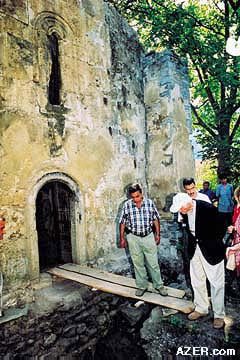

Left: Norwegian archeologists

believe that the Kish Church found in the foothills of the Caucasus

may be nearly 1,500 years old. It was built by Caucasian Albanian

Christians who lived in the region.

_____

Norwegians seem to have a particular - and some might even say,

vested - interest in Azerbaijan's early history. At the forefront

is the famous Norwegian anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl, 86, who

is convinced that Norwegians and other Scandinavians can, in

part, trace their roots back to Azerbaijan. Heyerdahl, who has

been featured in several issues of Azerbaijan International,

returned to Baku for the fourth time this past September to visit

the archeological dig in progress at Kish. But Heyerdahl is not

the only Norwegian to take a personal interest in this country's

ancient history.

The Norwegian

Ambassador, Olav Berstad, himself an archeologist by training,

is convinced of the wealth of archeological sites in Azerbaijan.

"There's more cultural remains beneath the surface of the

ground in this country than is generally recognized," he

insists, "and so little of it has been documented."

In the remote village

of Kish, six hours northwest of Baku, Norwegian and Azerbaijani

researchers are working together to learn more about the history

of the ancient Caucasus Albanian Christian church. Oral tradition

says that church was built in 78 AD, but the researchers place

it a few centuries later. In the remote village

of Kish, six hours northwest of Baku, Norwegian and Azerbaijani

researchers are working together to learn more about the history

of the ancient Caucasus Albanian Christian church. Oral tradition

says that church was built in 78 AD, but the researchers place

it a few centuries later.

Left: World-renowned Norwegian

anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl, 86, visits the archeological dig

at the Kish Church near Shaki, Azerbaijan in September 2000.

Photo: Sanan.

Caucasus Albania, not to be confused with contemporary Balkan

Albania in Europe, is the Roman designation for the northeastern

Caucasus, roughly today's Azerbaijan. Caucasus Albania remained

a cohesive, mostly Christian, political entity for about half

a millennium, from the 3rd to the 8th centuries A.D.

Berstad explains why the Norwegian government decided to help

Azerbaijan with this particular project: "We believe that

it's important for Azerbaijan, as a young, developing state,

to dig deeper into its past. Establishing direct links with the

past will strengthen the nation's identity as a separate entity

here in the Caucasus.

"Of course,

this project is also very interesting from a professional point

of view. The location is idyllic; Kish is a beautiful village

situated in the foothills of the Caucasus. It's obviously a very

old cultural site, and more needs to be known about it."

The project feeds the Ambassador's personal interests. "I've

been fascinated with archeology ever since I was a child,"

he adds. "I remember reading about Egypt, Central America

and the Indus Valley. I found early civilization to be so fascinating."

Berstad then studied archeology in Oslo for a short period of

time and received a scholarship to Leningrad in the mid-1970s

before beginning a career as a diplomat.

Team Approach

Despite a strong interest on the part of the Norwegians, Berstad

points out that the excavation and restoration of the Kish church

is an Azerbaijani project, not a Norwegian one. "It would

have come about sooner or later," he says. "But it's

happening sooner, since we have these established contacts and

have found some funds through Norway's Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

We would also like to use this project to establish a closer

professional relationship between Norwegian and Azerbaijani experts."

Various researchers

based in both Norway and Azerbaijan are working on the project.

In addition to Norwegian-American Storfjell and British Ms. Suseela

C. Y. Storfjell, there's Dr. Vilayat Karimov from the Academy

of Sciences' Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, who is

the local director of the project's excavations. Ms. Aliya Garahmadova

of the same institute is also involved. Archeologist Nasib Mukhtarov

has been responsible for organizing the local workers for the

dig. Various researchers

based in both Norway and Azerbaijan are working on the project.

In addition to Norwegian-American Storfjell and British Ms. Suseela

C. Y. Storfjell, there's Dr. Vilayat Karimov from the Academy

of Sciences' Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, who is

the local director of the project's excavations. Ms. Aliya Garahmadova

of the same institute is also involved. Archeologist Nasib Mukhtarov

has been responsible for organizing the local workers for the

dig.

Left: A very unusual grave

with six skulls was found near the foundation of the Kish Church.

Photo: Sanan.

Gulchohra Mammadova, Rector of Azerbaijan's University of Architecture

and Construction, is supervising what will be the restoration

of the church once the archeological project is completed. Mammadova

has spent the last 20 years investigating early Christian architecture

in Azerbaijan, a topic that has rarely been touched upon, even

though there are several other Christian sites in the country.

She was born in Yerevan, speaks Armenian and therefore managed

to read many of the Armenian historical books about early architecture.

She wrote the first monograph on the subject, "Christian

Architecture in Azerbaijan from the 4th to 14th Century".

Davud Akhundov, who directed Mammadova's thesis and was the first

scientist to claim that Azerbaijani architecture predated Islam,

has also contributed greatly to making the Kish project a reality.

Storfjell observes

that Azerbaijani scholars are not used to the Western multidisciplinary

approach to fieldwork. "It's very interesting to exchange

ideas with my Azerbaijani colleagues about methodology,"

says Storfjell. "They've been working in the Soviet tradition

and have had very little contact with the West. Though there

has been a common source and origin in our methodologies, they

have been developing separately and independently for quite some

time.

"In the West we are able to incorporate a number of scientists

in the actual excavation process. For example, on our digs in

Jordan, we bring along physicists, chemists, microbiologists,

paleontologists, geologists, climatologists, geographers, physicians

and even dentists. It's really a multidisciplinary team - like

a whole university - working on the site."

Another difference is that Western archeologists today are much

more focused on social elements and how ordinary people lived

thousands of years ago. "Fifty or 100 years ago," Berstad

explains, "archeologists were focused on learning about

the upper class and royalty. But this is only part of the story.

Today we have scientific tools and methods that make it possible

for us to know more about how ordinary people lived, what they

ate, and what kinds of diseases they suffered from. Modern science

has completely opened new possibilities into such studies."

The Kish project is organized through Norwegian Humanitarian

Enterprise, an organization with ties to the Lutheran Church

in Norway, which reaches out to the world through various humanitarian

projects. Norwegian Humanitarian Enterprise began working with

refugees in Azerbaijan in January 1994. According to Director

Tore Seierstad, the archeological project was brought to the

attention of the organization by Bjorn Wegge, a special advisor

when the humanitarian projects first started in Azerbaijan. "Wegge

is really the father of the project.

He was very interested in the history of this area and very knowledgeable

about the early Christian church. He started to look into the

history, spoke to historians and scientists here in Baku, read

books and soon found out that Christianity had early roots in

Azerbaijan as well. We went through Norwegian Humanitarian Enterprise

in Norway and set up the project as a Norwegian-Azerbaijani project."

Layers of History

Storfjell was amazed at the correlation between the building

that is standing today and similar structures in North Syria,

Jordan, Israel, Lebanon and Turkey but felt this was not to be

unexpected since those places were cradles of early Christianity.

"The Kish church was right at home among those Byzantine

structures in terms of both size and shape. In the Middle East,

the Islamic conquest basically put an end to the Byzantine era

in the middle of the 7th century - in 648 AD. But the architectural

style suggests that the Kish church might be earlier than that."

Though tradition and

legends hold that the church at Kish was built in the latter

part of the 1st century AD, Storfjell says that there has never

been any evidence of any church being built before the 4th century

anywhere in the world. The oldest known church to date is in

Aqaba, Jordan. Though tradition and

legends hold that the church at Kish was built in the latter

part of the 1st century AD, Storfjell says that there has never

been any evidence of any church being built before the 4th century

anywhere in the world. The oldest known church to date is in

Aqaba, Jordan.

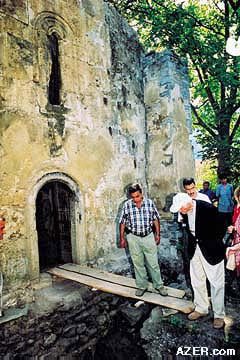

Left: After the excavations

and archeological surveys are completed, plans are being made

to restore the 1,500 year old church and convert it into a museum

to tell the story of the Caucasian Albanian Christians and their

religious faith. Photo: Sanan.

However, it seems clear that the site was in use long before

the church was built there. "Possibly, it has been viewed

as a holy place for millennia," observed Storfjell.

Archeologists have identified at least seven different layers

of data at the Kish site and believe that the church was reconstructed

at least four times. Each layer, or "stratum", represents

a period of occupation at the settlement. The earliest stratum,

naturally, is the layer on the bottom. Within the church building

itself, the archeologists have dug deep enough to reach sterile

clay, meaning that there are no cultural material remains lower

than this level.

In the oldest layer inside the church, ceramics were found that

date to the Early Bronze Age of the Kur-Araz culture, about 3000

BC. This calculation was based on the types of artifacts found

there - in other words, comparing them with other ceramics that

have been unearthed in Azerbaijan and determining if they were

made on a potter's wheel or shaped by hand, and how the clay

was worked and fired.

The next layer

indicates that the area was used as a graveyard prior to the

church's construction. Archeologists are not sure yet about the

dating of the burials, but estimate that they may have occurred

during the first few centuries AD. When Storfjell left Baku in

September this year, he carried out the bones of four different

people in his suitcases so that they could be dated using the

carbon-14 Method.

"We found a lot of skeletal material," Storfjell recalls.

"One grave was very unusual. It had one skeleton with all

of its bones connected in the right places, but on top of it

there were six skulls arranged in a sort of oval, right over

the lower abdomen and pelvic area. I've never seen anything like

it before. The skulls belonged to people who had already been

dead for some time when the other person was buried. They were

buried a second time with this person. It looked like most of

their other bones were there because there were enough femurs

(thigh bones) to account for the number of skulls that we had.

But they were carefully arranged - the femurs were in one area,

sort of grouped together. This grave predates the church."

Pieces of the Puzzle

Researchers are still trying to determine when the church was

built and exactly how it was used as a religious site, so that

they can place it within the larger context of Christian Caucasus

Albania and in the process leading from pre-Christian times to

the introduction of Islam. One piece in this puzzle is a coin

found near the church's foundation. Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, Curator

of Parthian and Sassanian Coins at the British Museum, dates

the coin to a Sassanian king named Kavad I, in the 39th year

of his reign, which corresponds to the year 526-527 AD. The coin

depicts a Zoroastrian fire altar and was minted near Persepolis

in what is now Iran. The inscription reads, "May the glory

of Kavad increase!"

"It's premature to draw a conclusion and say that the church

comes exactly from that same period," Storfjell cautions.

"What it gives us is the earliest possible date - it's hard

to imagine that it could have been earlier than that."

Evidence also seems to indicate that the building was a small

country church, only used by the people who lived in the village.

Kish is still a living village today. "We found very little

jewelry except for a few bronze pieces. This tells us about the

general economy of the area," Storfjell says. "There's

no evidence of mosaics on the floor; it was probably made of

stone or just plaster. Perhaps there was a monastery complex

associated with the church, as was often the case with churches

in the 5th to 7th centuries."

Albanian, Not Armenian

"We have clear evidence that this church was built as an

Albanian Diophysite church," says Storfjell. While Armenians

might beg to differ, he explains how the church's own architecture

shows it was not originally a Monophysite church.

"In the 5th and 6th centuries there was an intense theological

debate in the Eastern church regarding the nature of Christ,

whether he was both human and divine, or only divine, overshadowing

his human nature. At that time, the Caucasus Albanian church

took the position of the Diophysites, the group that perceived

Christ as having a dual nature - both human and divine. Today's

Western church, both Protestant and Catholic, also holds the

Diophysite position. The Armenian church, however, took the position

of the Monophysites, who said that Christ's nature was altogether

divine, even though he took on a human body.

"In a Diophysite church, the apse - the area where the altar

is located - is much closer to the level of the church's floor,

in order to symbolize the incarnation, or humanity, of Christ.

In the earliest phase of the church in Kish, the difference in

elevation is about 30-40 cm (1 foot, 4 inches), which shows that

they believed that God had come closer to humanity in the person

of Jesus. However, in the last three phases of this church, the

difference between the church floor and the apse was 70-90 cm,

which indicates a change in theology."

This doesn't necessarily mean that Armenians were actively using

the church, Storfjell says, only that it was influenced by Monophysite

theology. "The Armenians were not the only Monophysites.

There were also some groups in North Syria and North Iraq in

those early periods that held this belief as well."

"Armenians claim that any church on Azerbaijani territory

was built by Armenians," Mammadova says, a notion that has

contributed plenty of controversy to her own research on ancient

Azerbaijani churches. She argues that an ancient text proves

the Armenians wrong in this particular case: "In a 7th-century

text, 'History of Albania,' historian Moses Kalankatui writes

that 'the church in Kish is the mother of the Albanian churches.'

"Of course, there are also churches that were built by Armenians,"

she continues. "They built churches in Shusha, Karabakh

and Shamakhi. We don't deny that. But the origins of most Christian

churches on the territory of Azerbaijan are Albanian. In the

19th century, when Armenians were transplanted in Azerbaijan

from Turkey and Iran, they found these ancient Albanian churches

and monasteries that weren't being used. Instead of building

new churches, they renovated the existing ones that had fallen

into disrepair. Even though these churches now have Armenian

signs, they were originally Albanian, not Armenian," she

insists.

Telling the Story

Next year, the archeological team plans to excavate a 3 1/2-foot

(120-cm) trench along the foundation of the church. "When

we dig down through the soil," Storfjell says, "we

are digging down through time, layer by layer. Right up against

the wall and in the soil, we can piece together the story. If

you can date that material, then you can identify a date to attach

to the church.

"Archeology is a slow process," he says. "It requires

a number of seasons of excavation. We generally use a trowel

with a 4-inch blade. That's the one used by most American archeologists.

Smaller tools are used when we discover items such as skeletons

or jewelry."

The fieldwork is just one small part of the entire project, he

points out. "There's a lot of work to be done in analyzing

the finds and records that we have taken during the field portion

of the dig. We now have to try to make sense out of them. It's

like detective work.

"In the West, so little has been published about Caucasus

Albania. That's why it's 'terra incognito' for us. We're exploring

it for the first time. Obviously, this region was one of the

major crossroads on international trade routes from the earliest

civilizations. It's one of the richest archeological regions.

Evidence of anthropoid settlement from the Caucasus goes back

millions of years."

Although the church has not been actively used for religious

purposes nearly 200 years now, it is treated with great respect

in the community. There's a woman in the village, Ilaha, who

has a key and has been taking care of the site. Previously her

mother-in-law, Firangiz, did it. "They've done a wonderful

job," remarks Storfjell. "There's no damage to the

building - only natural deterioration."

Curiously, there is a folk tradition related to fertility that

has long been associated with the site.

Women who are unable to conceive visit the church, pray and press

a coin against the wall. Because of the humidity, the coin sticks

to the plaster. The next day, they return to see if the coin

is still adhering to the wall. If so, it's supposed to be a sure

sign that the woman will have a baby. The practice still exists

today, and villagers attest that even women from Baku come to

test it.

After the excavations are completed, the next phase will focus

on the restoration of the church by the University of Architecture

in Baku, with local Azerbaijani architects supervising and guiding

all aspects of the project. "Once the building has been

restored," Storfjell says, "the plan is for it to be

turned into a museum that will tell the story of the church from

its very beginning. When we are finished, we should have enough

evidence to be able to say something meaningful about the place

from when it was first used right down to the present time."

For more information about other archeological sites in Azerbaijan,

SEARCH for "Gobustan" and "samovar".

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.4) Winter 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.4 (Winter 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|

The

Kish Church

The

Kish Church