|

Autumn 2000 (8.3)

Pages

58-61

Bare Cupboards

Refugees

Struggle to Feed Their Families

by

Farida Sadikhova and Arzu Aghayeva

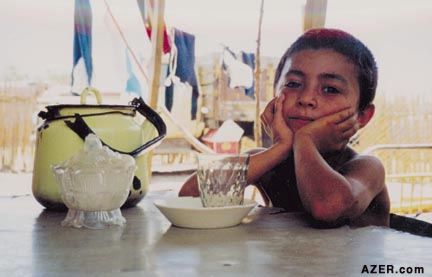

Above:

Tea is a

common substitute for food in refugee camps. Refugees drink it

to stave off hunger when there is little else to eat. Photo:

Abdusalimov

When

choosing the theme for this issue, we knew that we couldn't cover

food in Azerbaijan without talking about those who need it most

- the refugees. Nearly 1 million Azerbaijanis (one out of every

eight people) were forced to flee their homes because of the

conflict with Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh. Hostile foreign troops

still occupy nearly 20 percent of Azerbaijan's territory. Meanwhile,

tens of thousands of Azerbaijanis live in refugee camps throughout

the countryside, still waiting to return to their native lands.

This past July, we went to Sabirabad, about 2 hours southwest

of Baku, to learn how refugees cope when there is so little to

eat and no cash to buy food. For the 10,000 refugees who live

in this, the largest of Azerbaijan's refugee camps (Sabirabad

Camp No. 1), much of the day is spent doing manual chores: hauling

water, washing clothes by hand, gathering wood or dried manure,

making their own bread and trying to keep their families together.

These exhausting tasks are carried out by individuals already

weakened by malnutrition. Seven years in the camp have taught

them that the weather doesn't help matters, especially in summer,

which can be blisteringly hot. Amidst all these obstacles, we

wondered: how do they manage to survive?

_____

Ismat Aydinova, 34, is from the village of Ishigli in the Fuzuli

region. After fleeing from her home during the Karabakh War,

she ended up at the Sabirabad Refugee Camp in 1994 along with

her husband and their three daughters. Today her children are

15, 11 and 8 years old. They live in a one-room mud-brick shelter

that they built with their own hands.

One of the greatest differences between the home she used to

have and the refugee camp where they now live is simply not having

enough food. Ismat remembers: "We used to have a big garden

in our village with all kinds of fruit: cherries, pomegranates,

apples, pears, peaches and quince. We also grew vegetables like

tomatoes, potatoes, cucumbers, cabbage, onions, eggplant and

various green herbs. We didn't have to go to the market because

we already had everything we needed. We could cook whatever we

wanted: kabab, eggplant dolma, bozbash.

"We also got milk from our sheep and cow. We made our own

yogurt, so my kids could have ayran or dovgha (yogurt-based beverage

and soup) any time they wanted. Those were their favorite foods."

Water was nearby and crystal-clear. "We had our own well

and could drink ice cold water from it," says Ismat. "We

also had artesian water running from taps."

Day-To-Day Struggle

Returning to this former life seems like a dream for refugee

women, who now struggle to put any food at all on the table.

"We can barely make ends meet until the end of the month,"

says Ismat. "That's when the government gives us 20,000

manats per person, plus an extra 9,000 manats for each child.

Overall, we receive 120,000 manats (about $30) each month."

Monthly rations from

humanitarian agencies such as the International Federation of

Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRCRC) typically amount

to 5 kg flour, 1/2 kg sugar, 1 kg navy beans or rice and 200

g tea. There is rarely any assistance with meat, fruit or vegetables.

So what do you eat? we asked. "In the morning we have curds

(similar to cottage cheese)," says Ismat. "Just curds,

bread and sweet tea. Nothing more. Monthly rations from

humanitarian agencies such as the International Federation of

Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRCRC) typically amount

to 5 kg flour, 1/2 kg sugar, 1 kg navy beans or rice and 200

g tea. There is rarely any assistance with meat, fruit or vegetables.

So what do you eat? we asked. "In the morning we have curds

(similar to cottage cheese)," says Ismat. "Just curds,

bread and sweet tea. Nothing more.

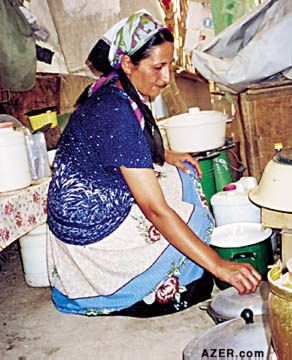

Left:

Refugees

are dependent on food rations such as flour from international

humanitarian agencies like the Red Cross. It has been eight years

now that many of these refugees have been living in camps because

of the Karabakh War. International aid is decreasing more and

more, which results in refugees being hungrier than ever. Photo:

Litvin

"Sometimes we eat twice a day, sometimes once, sometimes

three times," she says. "It depends on how much we

have to eat. When I say we have a meal, it doesn't mean that

we have something that can satisfy us. They're more like snacks.

Our largest meal is lunch - potatoes or occasionally, soup.

"Yesterday for lunch we had boiled potatoes. One potato

per person. In the evening we had tomatoes. Just tomatoes. Not

fried, just tomatoes by themselves, because they're cheap."

The refugees' diet depends completely on what's available at

the time. Mostly they make soups from tomatoes and potatoes.

Sometimes they have fried onion with eggplant, beans or macaroni.

Usually, they get these extra items with credit at a produce

stand in the camp.

Tomatoes, Tomatoes

"In the summer we eat mostly tomatoes," another refugee

mother confesses. "They're cheap, so we eat them all the

time - summer and winter. In the winter, we prepare dishes made

with canned or pickled tomato-soup or scrambled eggs with tomatoes."

Again, eggs are usually bought on credit and paid back when the

monthly assistance comes in.

Neighbors comment that in winter, they often eat pickled cucumber

and tomatoes with bread or make a thin broth with rice or noodles.

Even basic cooking ingredients like butter are nearly impossible

to get, though many of the residents used to make their own.

Ismat admits, "At home, we always had butter made from real

milk. It was imported from Moscow. But here we buy vegetable

oil. It's much different from what we used in our village. The

taste and quality is different. We have no other choice here;

we have to use vegetable oil."

Very Little Protein

Refugees eat very little meat, often no more than once a month.

One kilo of meat (lamb) costs about 10,000 manats (about $2).

Refugee mothers often buy only small portions of meat so that

they can eat it at two or even four meals. The meat may be ground

and stuffed in grape leaves to make dolma, or made into a broth

with potatoes, "sous". This month they had not yet

received any aid yet, so they had not eaten any meat.

Ismat likes to spread out the meat to last four meals. "I

buy it in four small portions - then I can cook a meat dish four

times a month," she says.

Other ingredients are also bought on credit. "In our camp,

there's a small store that belongs to a refugee," Ismat

says. "We buy things there like bread, macaroni, tea, sugar,

rice and flour, in small portions. We don't pay for the products

right away; we buy them on credit. For example, when there's

nothing to eat except bread, I have go and ask the store owner

to give me rice or macaroni."

"The vendor has debt lists for all of us," other refugee

mothers confess.

Only Bread to Eat Only Bread to Eat

Flatbread, the refugees' staple food, is made by hand- a time-consuming

and labor - intensive process. Ismat bakes two or three loaves

of bread every other day.

Left:

Living conditions

are so primitive in refugee camps. It's rare to have storage

space for any kitchenware. Saatli camp, summer 2000. Photo: Abdusalimov

She makes a yeast dough from flour, yogurt and a pinch of salt.

There's a tandir oven nearby, which is shared by ten neighboring

families in the wintertime. The oven is made of dried mud. It's

not built underground like some tandirs are. There's a special

cover on it, a sort of roof, to protect from the sun and rain.

"To bake the bread, we gather twigs and small pieces of

wood, place them in the tandir and build a fire," says Ismat.

"We slap the flat pieces of dough against the inner walls

of the tandir oven, making them stick. About five minutes later,

they're ready to take out. We never throw away the ash from the

tandir. We take it home and use it to warm up our mud-brick shelters

- especially in the fall and winter." Some of the neighbors

buy wheat and have it ground into flour. "We buy wheat in

Sabirabad," says a neighbor.

"It's 500-700 manats (about 25 cents) per kilo." There's

a mill in Sabirabad where the refugees can get the wheat ground.

Some people bake bread in a tandir, some on a saj (an iron disk

for baking bread or lavash). Some have simple kerosene burners,

and a few privileged ones have access to an electric oven. There's

a tendency to make more bread in the winter - eight or nine loaves

to last most of the week. But in summer the bread quickly gets

moldy, due to the heat.

No Refrigerator

Lack of refrigeration is a problem, especially during hot weather.

"I don't have a refrigerator here," bemoans Ismat.

"I had one before I became a refugee, but I couldn't bring

it with me when we fled. I barely managed to get the kids out

safely. Some people in the camp have refrigerators, but most

don't. So I can't keep food. If I make fried potatoes or macaroni,

we have to eat it all right away because there's no way to keep

the leftovers. Otherwise, we end up throwing them away."

Ismat says that she and her neighbors have improvised a partial

solution: "Our neighbor Orkhan, a 10-year-old boy, dug a

well in the ground, about 6 meters deep. There's water down there

that's not fit for drinking because it's very salty. But we can

manage to keep our cheese and bottled water cool just by lowering

it into the well. Things stay cool down there. When we need them,

we just pull them up."

Dirty Water

There is no indoor plumbing in these camps. The water hauled

from nearby taps is undrinkable, refugees say. "We drink

tea instead of water," says Ismat. "The water is full

of dirt, and not drinkable. When my kids are thirsty, I never

give them water - just tea with a bit of sugar. It's safer."

"There are water taps in the camp," she explains, "one

for every 20 houses or so. We get the water from those taps;

it comes from an open ditch or canal. They say it gets purified

in the cistern, that chlorine is added or something like that.

But the purification system is not very good as the water is

obviously dirty."

Even so, there are long lines, making the process of getting

water a very time-consuming chore. "The water is available

twice a day: from 8 to 9:30 a.m., and then again from 5 to 6:30

p.m.," says Ismat. "I usually go get water about 7:30

in the morning, or sometimes earlier. I get up early and go stand

in line. If you go at 8:00 a.m., you'll return at 9:30. We usually

carry the equivalent of about ten pails - about 50 liters - to

our homes.

"Then we boil the water, otherwise we wouldn't be able to

use it. Even then, it's still not pure. We used to have electricity

24 hours a day, so we didn't have a problem with cooking or boiling

water. But in the past year or so, sometimes the electricity

will go off and we've had to build a fire on the ground."

Left: Only a few kiosk-like stores exist in

refugee camps. Simply, there is so little money that most refugees

have to seek credit for the occasional purchase of macaroni or

flour, sugar or tea. Here potatoes and onions are for sale at

Saatli Refugee camp No. 1, summer 2000. Photo: Sadikhova Left: Only a few kiosk-like stores exist in

refugee camps. Simply, there is so little money that most refugees

have to seek credit for the occasional purchase of macaroni or

flour, sugar or tea. Here potatoes and onions are for sale at

Saatli Refugee camp No. 1, summer 2000. Photo: Sadikhova

Keeping Clean

The water hauled from the taps is used for more than just cooking

and making tea. "I use water from the communal faucet to

wash dishes," Ismat says. "After we eat, I wash the

dirty dishes in a wash basin. If the plates are not that greasy,

I simply rinse them in cold water. When they're greasy, I wash

them in warm water."

Taking a shower is a luxury that only comes once a week. "We

don't have a bathroom in our house," she explains, "but

there's a bathhouse in the camp. It's not so big, about the size

of a two-room apartment. It's divided into two parts: one section

for men, the other for women. It's open one day a week, from

3 to 10 p.m. It's always crowded." Some refugees opt to

wash with a little water in a bucket at their homes. It's a very

common practice.

Poor Growing Conditions

A casual observer may ask, "If refugees have so much trouble

getting food, why don't they just grow it themselves?" It's

not that easy, says Fariz Ismayilzade, Resource Center Coordinator

at the International NGO Hayat. "When we talk about refugees,

we have to remember that they had a completely different lifestyle

in their native lands," he says.

"They had pastures, they raised sheep, they planted gardens

and crops. When the refugees moved to camps, they lost their

traditional lifestyle. Even though they have enough space, the

growing conditions in the camps are very poor. They can't grow

the things that they used to grow in the mountains. So they've

had to change what they eat.

"Refugees in Sabirabad and Saatli may have access to a market,"

he continues, "but they don't have any money. I've seen

ducks and chickens running around in those refugee camps, so

apparently some of the refugees have a little 'property' of their

own. But inside their houses they don't have anything. They eat

from day to day and are unable to store anything."

"What can we grow here?" Ismat asks in frustration.

"First of all, we don't have any money. Second, the soil

is very salty, so nothing grows. When my youngest daughter sweats,

crusty salt appears on her skin. I think it's because we live

on very salty soil."

Showing Hospitality

If you visit an Azerbaijani refugee camp, you will immediately

notice that the refugees still believe in showing hospitality,

even though they can't lavish food upon their guests as they

once did. Fariz recalls taking some Italian journalists to one

of the Sabirabad camps last year.

"We stopped at some boxcars parked on a railroad siding

in the middle of nowhere, where six refugee families were living.

As we were leaving, I saw one of the refugee women offer some

lavash (paper-thin bread) to the journalists. The bread was really

dark, probably made from the worst quality wheat.

Obviously, it was all she had. I tried to offer the woman 10,000

manats (about $2.50), but she refused it. She gave but would

not take any payment, despite her destitute situation."

It's not uncommon for refugees to offer guests, especially foreign

guests, whatever they have, even when they don't know where their

next meal is coming from.

Having enough dishes is also a problem. "We own a total

of five glasses with saucers, five or six plates, and a couple

of dishes," Ismat says. "Sometimes when we have guests,

I want to treat them to tea, but I don't have enough glasses."

Weddings

If there's a special occasion at the refugee camp, such as a

wedding, the host usually buys food on credit, trying to make

the spread as festive as possible. These days at weddings, refugees

usually serve things like sous and dolma, but not usually pilaf

(rice). There might also be apples, pomegranates and quinces,

plus soft drinks like Fanta or Cola. When the guests come to

the wedding, they offer presents of money, which helps the host

pay the bills after the wedding is over.

One foreigner observes: "It's not uncommon that the talk

at the table is not about how nice the wedding is. Rather, it's

usually about the good times of the past."

Constant Heartbreak

Perhaps the worst part about facing these daily challenges as

a refugee is having to watch one's own children go hungry. "Look

at my kids!" Ismat exclaims. "They're so skinny and

pale. Sometimes, it's only bread that we have to eat for two

to three days at a time. Bread and absolutely nothing else. In

the summer when we often have just tomatoes to eat, my children

say that they have terrible pains in their stomachs. Maybe it's

because they're constantly eating the same food, or maybe it's

because the tomatoes are too acidic or spoiled."

She says that sometimes her children are too weak to get up and

do the simplest tasks. "My kids are not very strong. Sometimes

when I ask them, 'Go and bring me this or that,' they say, 'Mom,

I'm too weak, I can't go and bring it.' They simply don't have

any energy.

"Kids like to eat fruit. But the last time my kids ate fruit

was a month ago - they had some plums and a pear. Some fruit

sellers from the town came to our camp. We happened to have a

little money and bought some fruit. When we don't any money,

sometimes I go and exchange a kilo of flour for 2 kilos of fruit.

"It's very difficult for mothers to see their children go

hungry. I don't know what to do when my kids ask me for something

to eat. My younger ones often cry and say: 'Mom, they're selling

watermelons over there. Please buy us some!' But I don't even

have 500 manats (11 cents) to buy a watermelon.

"When I can't give my kids what they want, I feel really

depressed. My heart breaks, but I try not to show it. I just

tell the kids that I can't buy it. I try to explain our situation

to them.

"Sometimes my kids smell a neighbor cooking kabab and they

come running: 'Mom, there's a good smell coming from that house.

I want to eat what they're eating, too!' I try to distract them,

saying: 'No, it just seems that way; they're not cooking anything.'

I try to make them believe that they didn't smell anything. It's

a lie, but I have no other choice.

"Many times when I see that my kids are hungry, I give my

share of food to them. My youngest daughter notices and asks:

'Mom, why aren't you eating?' I tell her: 'Don't worry, I've

already had my share.' How can I eat when my kids are hungry?"

Most refugee kids learn from an early age to keep quiet about

their wishes. They see the situation and understand. There are

no jobs - nothing. The neighbors are all in the same situation.

Everyone is poor.

Risk of Disease

Malnutrition makes refugee children vulnerable to another threat-disease.

With no money for medical treatment or supplies, refugee parents

watch helplessly as their children suffer from diseases like

scabies, influenza, malaria and tuberculosis.

Fariz says, "In the Sabirabad refugee camp, I met a woman

who was 35 years old, but she looked more like 50. She had two

little children. I was showing a foreign journalist around. Suddenly

the woman started screaming: 'Come here! Come here!'

"When we went over to where she was, she told us that she

had tuberculosis and that nobody was helping her. She called

her kids to come out of the house. They were so thin and probably

had not had any meat in a long time. She said that her children

would soon have tuberculosis, too. She was desperate and wanted

to ask local and international organizations to help."

Decreasing Aid

What do the coming years hold for Azerbaijan's refugees? At least

in the immediate future, prospects look grim. Refugees will tell

you that during the past eight years they've been living in the

camps, the situation has gone from bad to worse. "We don't

receive as much food as we used to," they say. "Plus

our children are growing up. They need more food and they need

clothes."

Food rations are being cut back or eliminated altogether. "We

used to get yellow peas as humanitarian aid," says Ismat.

"Sometimes we would exchange the peas for curd: a kilo of

curd for a kilo of peas. A kilo of curd costs 1,000 manats. But

now we've been cut off from receiving the peas. We don't know

what the future will bring. We don't know what we're going to

eat."

Food isn't the only provision that's been cut back, she observes.

"We used to get 30 liters of fuel as humanitarian aid each

month. We use the fuel in the stove to keep the house warm. We

received it as part of the humanitarian assistance from Iran.

But now the supply of kerosene has been cut off because the aid

has been decreased. We're concerned about how we're going to

keep our house warm."

A New York Times article reports that UNHCR's (United Nations

High Commissioner for Refugees) budget for Azerbaijan has been

reduced from $12 million last year to $4.7 million. Fariz says

that other organizations are also reducing the amount of goods

given out to refugees. "Instead of giving out direct humanitarian

assistance, NGOs are developing more and more training programs.

Most humanitarian organizations think that the crisis period

of refugees - 1993 to 1995 - has already passed. For example,

Hayat has been doing training on conflict prevention, legal rights

and business skills. Instead of giving out food, as we were doing

in 1994, we're doing more training."

Even though the Azerbaijani government reached a cease-fire with

the Armenian forces in 1994, there is still no peace agreement,

so refugees are not able to return to the lands that they call

home. Many of them have been waiting for eight years. Though

still eager to return, most of them doubt that it will happen

anytime soon.

"When neighbors gather, we often talk about food shortages

and curse those who drove us to such poverty," says Ismat.

"We often talk about the 'good old days' when we ate kabab,

kufta and dolma. We want to go back to our lands and grow vegetables

and fruits there. We don't want to stay in this camp forever."

Special thanks to Vugar Abdusalimov of UNHCR for facilitating

the visit to Sabirabad refugee camp and to Fariz Ismayilzade

of Azerbaijan's first Humanitarian Association, Hayat, for providing

background material. Farida Sadikhova and Arzu Aghayeva

are AI staff members.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.3) Autumn 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.3 (Autumn 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|