|

Autumn 1997 (5.3)

Pages 21-23

Cinema and Censorship

A Glimpse

of the Former Soviet Union

Conversation with

Screenwriter Rustam Ibrahimbeyov

by Betty Blair

See also:

Famous People: Then and Now - Rustam

Ibrahimbeyov

Burnt

by the Sun - Winner of Oscar

Rustam Ibrahimbeyov (pronounced roo-STAM ee-brah-him-BEH-yov)

has been one of the driving forces in cinematography in Azerbaijan

since the late 1960s. A renowned screenwriter, he currently heads

the Filmmakers' Union of Azerbaijan as well as the Confederation

of Filmmakers' Union (CFU), which represents filmmakers from

all of the former Soviet republics. Unlike many other former

associations and institutions of the USSR, every single republic

has maintained strong ties with the CFU even after the demise

of the Soviet Union. A great deal of credit for this should go

to Rustam Ibrahimbeyov who currently serves as Acting Chair.

Rustam has written scripts for more than 30 films, most of which

have been produced and many of which are widely acclaimed. "In

a Southern City" (directed by Eldar Kuliyev, 1969) was the

first film to raise serious moral issues about the Soviet system.

"White Sun of the Desert" (directed by Vladimir Motyl,

1969) is legendary, and Russian cosmonauts consider it a good

omen to watch before they prepare for a launch.

|

|

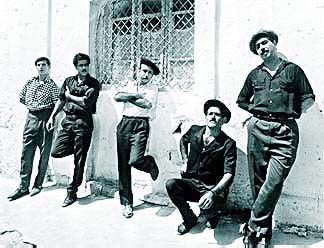

Above: Scenes from "In a Southern Town"

(Bir Janub Shaharinda), Eldar Guliyev (director), Rustam Ibrahimbeyov

(screenwriter), 1969. One of the first films ever produced in

the Soviet Union to challenge the social-political establishment.

He has received numerous awards from the Soviet Union, and now

since the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991), he's been recognized

at international film festivals as well. All Union Prizes were

given for "White Sun of the Desert," "Interrogation"

(directed by Rasim Ojagov, 1979), "Double Life" (also

with Ojagov, 1987) and "Then I Said: No!" In 1990 the

Istanbul Film Festival awarded "Guard Me, My Talisman"

(directed by Roman Balayan) with the Golden Peacock Award. The

following year "Urga, Territory of Love" (directed

by Nikita Mikhalkov) and known in the U.S. as "Close to

Eden" won the Golden Lion Award in the Venice Film Festival

as well as the Felix Award in Berlin as Best European Film. "Close

to Eden" was also nominated for an Oscar in 1992 as Best

Foreign Film.

Left: From "Another Life" (Ozga Omur), 1987.

Directed by Rasim Ojagov. Alexander Kalyagin plays Farid Rezayev

and Irina Kupchenko plays Lilia. Left: From "Another Life" (Ozga Omur), 1987.

Directed by Rasim Ojagov. Alexander Kalyagin plays Farid Rezayev

and Irina Kupchenko plays Lilia.

Rustam was involved with Nikita

Mikhalkov in all stages of the development of "Burnt by

the Sun" which had the distinguished honor of winning both

the Grand Prix at the Cannes Festival (1994) and Best Foreign

Film at Hollywood's Academy Awards (1995). That, in itself, is

a rare feat since popular tastes usually differ immensely between

North America and Europe.

"Urga" and "Burnt

by the Sun" received the Russian State Prize which

was presented by President Yeltsin in 1993 and 1996, respectively.

Rustam is currently juggling a variety of projects in numerous

locations around the world-Moscow, Baku and Los Angeles. Filming

for "Barber of Siberia" (directed by Mikhalkov, 1997)

was recently completed in Prague and is soon to be released.

Two of Rustam's screenplays are being used in American film projects

with the renown Australian director Vincent Ward and famous screenwriter

Don Jacoby. Oleg Safaraliyev is in preproduction with one of

Rustam's screenplays at Azerbaijan's national film company, Azerbaijanfilm.

A full feature film, "Mystery," is being shot in Georgia

under the direction of Mikhail Kalatozoshvili, and Evgeny Mitrofanov

is nearly ready to debut the low-budget film, "Don't Touch

Scorpio's Ears."

Despite Ibrahimbeyov's broad and successful international involvement

as a screenwriter, he remains deeply committed to his filmmaking

colleagues in Azerbaijan and to the revitalization of Azerbaijan's

film industry. As such, he has become both the catalyst and the

driving force to establish the Baku International Film Festival

which he hopes will premiere in the autumn of 1998 and become

a world-renown annual event.

The following conversation took

place between Rustam Ibrahimbeyov and Azerbaijan International's

Editor Betty Blair in Baku at the Cinematographers' Union in

June 1997.

_________

I'm interested in the problems that you experienced with censorship

during the Soviet period. In the West, we were always led to

believe that everything was controlled by Moscow, and that all

art forms, especially film, had to be intensely scrutinized and

"politically correct."

When it comes to censorship in the former Soviet Union, I've

had a lot of experience as I worked simultaneously in three artistic

areas-theater, literature and cinema. These represented three

distinct censorship systems in which the level of centralization

varied. Literature was the easiest to get cleared, since all

decisions were made on the level of the local publishing house.

In my experience, literary censors seemed most concerned about

disclosing information that might be considered military secrets.

However, restrictions imposed on movie makers were much more

stringent. Ultimately, you're right. The final decisions were

made in Moscow as this art form was considered the most powerful

tool for mass propaganda. Lenin once observed, "Cinema is

the most important of all arts."

Stalin, too, appreciated its significance. He was known to have

watched all the films that were made in the Soviet Union. As

he didn't have much time, such a policy severely restricted the

production of movies from the mid-30s until his death in the

early 50s. Stalin believed in creating only a few movies, but

making sure they were of superb quality.

For cinema, there were six levels of censorship-the initial three

in Baku, followed by three in Moscow. A film could be rejected

at any stage. Topics were categorized either as "passable"

or "non-passable." A film with a "non-passable"

theme was dumped at the first level-absolutely rejected.

Passing all those levels must have taken a lot of time.

It was a very complicated, time-consuming process. No script

managed to pass all the levels in less than six months. But sometimes

it took three, four or even five years.

Could the authorities be bribed?

Bribing never worked as far as ideology was concerned. Perhaps,

now and then, it might have salvaged some movies which were of

low technical quality, but the censors never made any concessions

when it came to ideology.

Was there a written set of instructions saying what you could

do and what you couldn't? Or were these things just understood

informally?

There were no written stipulations. But you must understand

that through this phenomenon of the Soviet government, which

ruled over us for 70 years, a new type of human being began to

evolve. Their ideology penetrated us like a laser beam and led

to a moral mutation in our being.

We knew from childhood exactly what we could say at school, at

home, to friends, relatives or to anyone else. A child hearing

his father curse the Soviet power at home never talked about

it at school or in the street, even though no one had warned

him: "Don't talk about it." The Soviet system created

a new type of human being who understood such things without

being told. Each of us developed a high sense of intuition. To

succeed, we had to.

Let me give you an example. The young son of one of my friends

didn't like nursery school. Nevertheless, his parents forced

him to go. One day the children were singing a song praising

the nursery. The father saw his son join in. When he asked him

about it later, the lad replied, "Dad, it's impossible not

to sing that song!" So, you see, even a five- year-old child

knew what was expected and what he had to do.

What were the "songs" you had to sing when it came

to making films?

These were songs serving, praising and glorifying the Soviet

system and socialism. Cinema was supposed to inspire people with

the idea that life was wonderful, that people were happy. If

there was a single mention of death, illness, poverty, or unhappiness,

the screenplay was at risk. The censorship committees were likely

to ban it as "non-passable." The government's goal

was to convince people that they were happy, and that this happiness

was due to the socialistic system. People, in turn, were dutifully

expected to serve it forever.

Was there any way to get around that?

Let me describe how the process worked. Take Shakespeare's

"Othello" for example. If you had wanted to produce

such a film, you could never have disclosed in the application

that Othello would commit a murder. Rather, you would have said

that the movie was about a brave general who was successful in

battles, who defended his country and loved his people-things

like that. You would have also mentioned that there was another

general, unfaithful to his motherland, who envied the other general,

and that the story basically was about the eternal struggle between

good and evil.

Left: Jafar Jabbarli (1899-1934) screenwriter and dramatist.

He's famous for films such as "Sevil" about the unveiling

of women. He is revered as one of the founders of cinematography

in Azerbaijan. The national film studio, Azerbaijanfilm, is named

after him. Left: Jafar Jabbarli (1899-1934) screenwriter and dramatist.

He's famous for films such as "Sevil" about the unveiling

of women. He is revered as one of the founders of cinematography

in Azerbaijan. The national film studio, Azerbaijanfilm, is named

after him.

The plot had to be summarized concisely in five or six sentences

on your application. Actually, this was often the most difficult

step because those few, carefully chosen words had to be persuasive

enough to get the project rolling.

It was very easy for your story to be rejected if the ideology

seemed dubious or out of line. But later, when you had a screenplay

in hand-a literary piece that was already developed-especially

if it were well done, they couldn't reject it as easily, no matter

how strict the censors might be. Don't forget, censors were highly

qualified people. In fact, they were intellectuals, and they

knew how to identify quality work.

Let me return to our hypothetical case of "Othello."

The procedure went as follows. After they granted permission

to develop the screenplay, then you would have to defend it on

the second level where they would have noticed the disparities

between what you had described in your application and what actually

had been scripted. Shocked, they would have asked, "What's

this? How could you do this? You promised to write about the

deeds of a heroic general. But here, you've written about a jealous

man who kills his wife!"

Then you would have had to defend your idea. "OK. Let's

find a way to do this. Let's make her so terrible that killing

her is justified." And together, you would have had to develop

a rationale for the hero's behavior together with the censor.

The screenplay then would have to go to a third level, the Arts

Council, which was a group of about 30 people from various professions.

Since each one could express an opinion at that stage, it had

the potential for some very solid constructive criticism to emerge.

In the course of the discussion, you would have tried to use

the Arts Council's comments to "correct your mistakes"-that

is, to eliminate what you had been forced to introduce at the

previous level.

Can you give me a concrete idea of this in your own work?

The most striking example was my screenplay for the film,

"In a Southern Town" (1969), in which the hero was

obliged to avenge his sister's honor. Simply, the rules of the

street required that he stab and kill his neighbor who had been

engaged to marry his sister, but who had left her for another

woman.

The censors in Baku didn't like the script. They insisted that

Azerbaijanis were civilized, and such behavior was inappropriate.

They tried to persuade me to tackle a different subject: "Why

don't you write about oil workers or scientists and their achievements?"

They noted that in the application I had written that the screenplay

was about an oil worker and his work. Well, it was true. My hero

was an oil worker. But in my original application, I had not

revealed that he was going to kill or injure anyone.

The censors at the second stage made me introduce a few scenes

to show that "one of my heroes is an oil worker, another

is an engineer"-obviously, elements of a civilized society.

The Arts Council, however, found such scenes weak and irrelevant.

So, I used their comments to get them eliminated. This enabled

me to pass to the fourth level in Moscow.

Well, it turns out that Moscow was not bothered or offended in

the least that I had depicted Azerbaijanis as wild and uncivilized.

They said: "Bravo! You've touched on a critical problem."

On the other hand, they did show concern about the characterization

of my policeman. I had shown the policeman pretending not to

see the murders and the fighting that took place right in front

of his eyes. "This depiction seems rather weak. This is

not the way a Soviet policeman would act," they balked.

So the Moscow censor made a completely different evaluation about

Azerbaijanis, and I was able to proceed as originally planned.

The fifth level was a regional editorial board. It was here that

an official might say, "You know, we really can't accept

this screenplay because something similar has just been written

in Kazakhstan (or Moldova or some other republic). We can't have

two or three films produced in the same year that are so much

alike." And so the screenwriter could choose to wait for

another year or start all over with another topic.

The final "yes"-the sixth step-came only from the top,

from the Deputy Chairman of the State Cinema Committee of the

USSR.

Were you free to move ahead then?

No, not really at all. When the director started filming,

a separate editor was assigned to each project to make sure everything

corresponded to the way it had been approved. Even the slightest

deviation could bring filming to a halt.

There were even occasions when a film had been completed and

then not allowed to be released. That's what happened to "In

a Southern Town." Remember, Moscow ac-cepted it. But Baku

made such an uproar that they brought it up for discussion at

the Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of

Azer-baijan, the highest local authority at that time.

After watching the film, the committee members concluded that

the film was a disgrace to Azerbaijan. Fortunately, however,

the person in charge of the Ideological Department of the Committee

was Jafar Jafarov. He was a theater buff, an intellectual and

a highly cultured person. When others condemned the movie, he

dared to say how much he liked it.

At the same time, the Moscow newspaper, "Komsomolskaya Pravda,"

published an article praising the movie. (A Moscow journalist

had come to Baku and watched the film.) So Jafarov started arguing

with the critics. It was the first time in the history of Azerbaijan

that a film generated so much public discussion prior to being

released.

Why were they so sensitive?

They argued bitterly over it. "Azerbaijan is a civilized

nation. The people here are intellectually advanced and concerned

about the problems of the state and its production. But here

you are showing us as criminals. You are showing us as backward

people."

I told them that the underlying theme was quite different, and

that the film was actually intended to show how environmental

and social forces make people do things that they don't want

to do. I told them I could have written an identical story set

in a research lab where the atmosphere made people act in a way

that contradicted their spirit and nature, too. I just happened

to choose the streets of Baku because that's where I had grown

up. I knew those streets very well.

Heated discussions ensued, and the majority, but not all, of

the Azerbaijani intelligentsia expressed opinions that contradicted

the Central Committee. Intellectuals like Rasul Reza and Azad

Mirzajanzade stood up and defended me. In fact, it was Rasul

Reza, the father of the famous contemporary writer Anar, who

told a fable to illustrate his point.

He reminded the assembly about Lion who, as the story goes, had

a splinter stuck in his paw. Each animal, in turn, had come up

and licked Lion's paw, easing the pain for a short while. But

soon the paw would start throbbing again. Then Rabbit came and

pulled the splinter out of Lion's paw. The process was so painful

and infuriated Lion so much that he devoured Rabbit. Shortly

afterwards, the pain ceased, and Lion realized what he had done

and became very sad. Rasul Reza told this story, convinced that

there was a correlation between the activity of the committee

towards my film and the fable.

Would you say this was a special turning point in your life?

Without a doubt! This was the first time I had ever struggled

with this monster-the Soviet Union. I gained enormous confidence

from the ordeal. The fact that I won, clearly shaped my future.

Had I lost, my life and career, doubtlessly, would have taken

quite a different turn. This was considered my first film, although

another was being produced at the same time.

A week later, two articles appeared. Curiously, they contradicted

each other-one praised the film; the other, criticized it. They

appeared in two different newspapers, but both belonged to the

Communist Party Committee.

Despite my victory, my next screenplay was stopped. It took me

15 years to finally produce it. Entitled "A Business Trip,"

it was the story of a young man who had come to the city from

the village to collect a loan that someone had borrowed from

his family many years earlier. But in the process of trying to

get the money back, the villager becomes so absorbed with city

life that he forgets about going back.

Why was the film stopped?

The censors asked, "What kind of topic is this?"

They were irritated by the fact that I was not using one of the

"great" themes which praised socialism and the Soviet

power. They wondered why I was writing about someone who wanted

to take back a loan. The truth was, in fact, that I was not struggling

against Soviet Power, I was simply ignoring it.

What were you trying to say in the movie?

Again, I wanted to show how values change, how one's attitude

towards life changes under the influence of one's environment.

After the movie was stopped, I started writing plays. Theater

was less centralized than cinema. If I managed to get it accepted

in Azerbaijan, then it could also be produced in other republics

without gaining permission from Moscow. The Ministry of Culture

of Azerbaijan had more freedom than the Azerbaijan State Film

Committee.

Let's talk about your other works. You've written more than

30 screenplays in the past 25 years. Most of them have made it

into films. Which do you consider your best?

It's difficult to say-probably "Burnt by the Sun."

It won the Academy Award for "Best Foreign Film" in

1995. The story line focuses on Stalinism and its devastating

impact on the life of an individual Bolshevik colonel. It deals

with the purges made during Stalin's regime.

The main image-the "Sun"-represents Stalin. We wanted

to say that totalitarian systems are governable or manageable

but only up to a certain point. Afterwards, they take on a life

of their own, destroying not only those whom they were originally

intended to destroy but their creators as well. Specifically,

we had in mind the immense system of the Soviet Union. We weren't

blaming anybody. We were merely showing how everyone became a

victim.

Could you have produced this film during the Soviet period?

I think so. No doubt, it would have been impossible when

Stalin was alive when hundreds of thousands of people-virtually

anyone suspected of questioning the communist system-was hauled

off to labor camps in Siberia. But after Stalin's death in the

early 1950s, yes, I believe, we could have made such a film.

What other types of symbolism did you use to skirt censorship

issues during the Soviet period?

We often drew upon what might be called "modeling"-just

as a globe is a model of the Earth. For example, we would use

a single family or an individual courtyard to represent an entire

society. One example is my screenplay called "In Front of

the Closed Door." It tells a story about people living in

the same building who hear a woman screaming who lives in one

of the apartments being beaten by her husband. They hear her

hysterical sobbing every day but pretend not to notice. No one

shows any concern for her as a needy human being although they

all make her the primary target of their gossip.

The film focuses on what happens in front of the door rather

than behind it. Obviously, the story is not really about the

woman; it's about people who are uncaring and passive. The screaming

woman symbolizes the suffering that everyone was ignoring. I

wanted to typify what I felt was the main problem of the Soviet

people-the problem of indifference. People tried not to notice

all the problems going on around them. They saw them, but they

kept insisting that everything around them was fine.

You've made films both inside the Soviet Union, and now since

the collapse of the USSR, abroad in Europe and the United States.

How do you compare the process of getting a script accepted in

the West with the stringent censorship that you dealt with during

the Soviet period?

To tell you the truth, I'm not sure it's easier to sell a

screenplay in the States than it was to pass through those many

stages of censorship during the Soviet period. In America, there's

a different sort of censorship-but nevertheless, similar obstacles.

I'm referring to what might be called the "censorship of

taste."

In the Soviet Union, the State gave orders, designating which

screenplays could be developed. But in the West, commercialism

rules. If someone invests in your script, obviously, they're

looking for millions of people to like it. That's only logical.

After all, that's what the capitalistic system is all about.

But it's difficult to create a script that masses of people can

truly appreciate. In essence, popular taste and the subsequent

commercial decisions shape the criteria for films in the West.

I'm not sure which system is really easier to deal with. Time

will tell.

An earlier conversation with Rustam Ibrahimbeyov was published

after "Burnt by the Sun" won the Academy Award for

Best Foreign Film in 1995 (for which Rustam wrote the screenplay).

See "The Scorching Sun and the Nature of Totalitarian Systems"

in Azerbaijan International, AI 3.2, Summer 1995.

From

Azerbaijan

International

(5.3) Autumn 1997.

© Azerbaijan International 1997. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 5.3 (Autumn 1997)

AI Home | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|